by Caroline Gwaltney

Some might think of the 1920s as the lull between the end of the Great War and the Stock Market Crash. But on the University of Alabama campus, these were years of excitement that saw the football program rise to national power under head coach Wallace Wade, with its first Rose Bowl victory and undefeated season. Worlds away, in California, the film industry was blossoming as moving pictures became big business. Silent features were the predominant product early in the decade, having evolved from vaudevillian roots. But productions were becoming bigger, longer, costlier and more polished. By 1929, there were 20 Hollywood studios, and the demand for movies was growing by leaps and bounds.

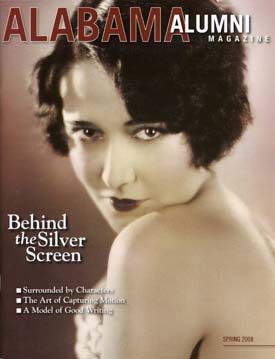

It was during this time that two small-town students experienced both the growth of the Capstone and the glitz and glamour of Tinseltown—Johnny Mack Brown and Dorothy Sebastian—contemporaries who made it big on the silver screen. And unlike many actors of their day, both successfully made the transition from silent films to “talkies.”

Under Western Skies

You could say it was more than a football game. It was the chance to avenge the South, to reclaim the valor and honor of the “lost cause.” No longer would the region be known primarily for its poverty and illiteracy; it would be the home to some of the best powerhouses of football in the nation. For the first 50 years of college football, the game was dominated by such consistent rulers as Yale, Army, Notre Dame, Michigan, Stanford and Southern California. According to prevailing sentiment, Southern boys couldn’t compete.

And so the stage was set. The University of Alabama football team, showcasing the talents of the runner known to sportswriters and fans as the Dothan Antelope, played the University of Washington in the 1926 Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Calif. Johnny Mack Brown, the All-American halfback, went to work on passes of 48 and 63 yards and then added on two inspiring runs. Washington was the overwhelming favorite going into the game, and proved so with an early 12-0 lead. Wade, in his half-time, locker-room speech, said, “And they told me Southern boys would fight.”

In the second half, the unbelievable happened. Quarterback Pooley Hubert, the seasoned and mature team leader, kept running straight into the Washington line until he scored. But the real story was Brown—the dashing running back caught a 50-yard pass in full stride and made a touchdown. Everyone in the stadium was stunned at Alabama’s 20-19 victory, including the winners. “Pooley told me to run upfield as fast as I could,” recalled Brown after the game. “When I reached the three-yard line, I looked back and sure enough the ball was coming over my shoulder. I took it in stride and went over, carrying somebody. The place was really in an uproar.”

There was more to come in Brown’s legendary accolades, though. Sure, part of his legacy is as an All-American champion of the college gridiron, but the other part is being one of the most popular Western movie entertainers during the heyday of the Hollywood cowboy. From the backfield to the big stage, this success story reads better than any screenwriter could have imagined.

Brown was born in Dothan, Ala., on Sept. 1, 1904, to Harry John Henry Brown, a shoe merchant, and Hattie McGillivray Brown. He was one of nine children, and sports was a keen interest among all of them, which eventually paid helpful dividends for the family. Five of the brothers were recruited to play football at UA, and supposedly Johnny Mack was not the most talented. He stood out in the group by making his way to early athletic stardom in a myriad of sports, excelling in high-school track and baseball, along with football.

In 1923, Wade became the coach at Alabama, and Brown made his arrival as a player. His best assets were natural ability and speed. Teammate and fellow Hall-of-Fame inductee Wu Winslett could only describe him as “one heckuva player.”

Along with his athletic prowess, it turns out that Brown was an eager participant in on- and off-campus dramatics. There is some discrepancy on how the Hollywood connection was originally made. Some say he had his first encounter during the 1925 season, when director George Fawcett received sideline passes to an Alabama football game where he recognized that Brown had idol potential and urged him to visit California for a screen test. Another version suggests that Fawcett simply asked Brown to look him up. When he was an assistant coach for Alabama in 1927, Brown told a group of people that he went to the Rose Bowl game and took the screen test during that visit.

Regardless of how he was introduced to the entertainment industry, the result was that Brown signed a five-year MGM contract and began his career with small parts in Slide, Kelly, Slide!, Mockery, After Midnight and Bugle Call. Larger roles quickly followed inThe Fair Co-Ed with Marion Davies and Our Dancing Daughter with Joan Crawford, among others. He married his college sweetheart, Cornelia Foster, and they moved to the West Coast for Brown’s career. They had four children: a son, John Lachlan, and three daughters, Jane Harriet, Cynthia and Sally.

It didn’t take long for Brown’s true specialty to shine through—cowboy acting. He made his Western debut in 1930 in Montana Moon, also co-starring Joan Crawford. He reached instant popularity in the genre with his next part as Billy the Kid, in which he learned the finer points of gun twirling from William S. Hart. Still, Brown never forgot his Southern upbringing and arranged for Billy to premiere at the Bama Theatre in Tuscaloosa. Even his Southern drawl, which early mentors went to great lengths to correct, became a real asset.

Brown was featured in two Western serials in the next two years and then began his own series of free-standing films when he signed with Supreme Pictures in 1935. Next, he went to Republic Entertainment Inc. to appear in eight more.

In 1939, he teamed up with Universal, and during this period was consistently ranked among the top ten cowboy stars. This led him to the 1943-52 classic Monogram, a project that was extended to nearly 65 pictures. His notoriety expanded with a radio show, Under Western Skies, which ran from 1940 to 1950. He remained popular through the ’50s as the hero of a series of comic books. Retiring in 1952, he died from kidney disease on Nov. 14, 1974, in Woodland Hills, Calif. By official count, he appeared in 168 films.

Brown’s movie character was always a rough, tough, no-nonsense kind of guy, quick to pull the trigger if it meant bringing justice. Upon returning to Alabama in 1969 as a charter member into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, he said that in a lifetime of shootouts on screen, he had been defeated only three times, therefore claiming victory the other 297 times. “But I treasure this more than anything,” he said during his induction.

The handsome college athlete turned Hollywood cowboy said he never expected the way his life would turn out. “I’d never ridden a horse before I got to Hollywood,” he once admitted. “But I’d ridden a lot of mules. If I hadn’t gone into pictures, I’d probably either be in coaching or walking behind some old mule somewhere.”

Sackcloth and Scarlet

During a time when women were being given their first legal rights, Dorothy Sebastian still wanted more. The lights and glamour of the silver screen shined brighter than anything she had seen growing up in Birmingham, Ala. But making it to stardom is never an easy goal to reach, so she needed just a little luck.

For Sebastian, that meant taking chances in order to find opportunities. Getting to Hollywood meant going to New York City first, where she tried to make it as a dancer–something she always wanted to do as a young girl. It also meant leaving her studies at The University of Alabama. Her parents disapproved of her desire to be a dancer or actress, so when she ran away from home, she was quickly forced to return. In order to convince her parents she could support herself in preparation for a second move to New York, she made and sold portrait sketches, parchment lampshades and cushion covers, even going as far as opening a little shop in Birmingham.

The second time she went, she told her family, “I’m going to New York to study art,” and said she would be staying with a maiden aunt, neither of which actually occurred.

What did happen was continual rejection by theatrical agents–but her ambition was not stifled. One of her first jobs in the city was with the Ned Wayburn fashion show. That held her interest for a short time, and then Sebastian decided it was time to try the theater again. She went to a casting call for Scandals, a string of Broadway musical revues produced by George White, modeled after the Ziegfeld Follies. Even though the casting was closed, a chance meeting with White, sheer determination and her thick Southern accent got her a place in the chorus. She also got a nickname from the producer that stuck with her throughout her career—Little Alabam.

Most accounts indicate that she was born Stella Dorothy Sabiston (she changed the spelling of her last name after leaving home) on April 26, 1903, in the Woodlawn area of Birmingham. Her parents were Lycurgus (Lawrence) Robert and Stella Armstrong Sabiston. A recurring theme throughout her life was confusion about her exact age, since like many Hollywood A-listers of the era, she wanted to seem younger, and therefore gave inconsistent answers about the year of her birth. She once told a magazine reporter she was 15 when she moved to New York, although census reports attest that she was 20, and details from her first marriage license indicate she would have been 22 at the time.

Sebastian married three times, the first time in 1920 to Al Stafford in Birmingham. That union ended in divorce in 1924, before she left for the Northeast.

Following her stint with Scandals, she earned roles on the big screen after befriending a movie producer at the Ritz Carleton. She began a whirlwind film career with her first role in Sackcloth and Scarlet, released in 1925.

Her second marriage was to fellow actor William Boyd, who had gained fame in the immensely popular Hopalong Cassidy movies, playing the cowboy-hero created by author Clarence E. Mulford in a series of stories and novels. They met while filming His First Command in 1929 and then worked together again in Officer O’Brien. The second of these turned out to be somewhat of a flop, and as the story goes, they fell in love while consoling each other. The last movie they worked together in was The Big Gamble, and by that time they were man and wife. Their marriage ended in divorce in 1936.

In 1946, she became Dorothy Sebastian Shapiro after marrying Herman Shapiro. They remained together until her death from colon cancer in 1957.

Another well-known aspect of Sebastian’s personal life was her affair with Buster Keaton, the comic actor and filmmaker, which lasted from two to 10 years, depending on which biography you read. The relationship was an open secret in Hollywood, as Keaton was in an unhappy marriage to Natalie Talmadge, and supposedly fell for Sebastian because she was the polar opposite of his wife—fun, full of life, liked practical jokes and enjoyed playing bridge.

It was common knowledge that Sebastian enjoyed the excesses that went along with being a star—the all-night parties, club hopping and extravagant dinners. Apparently she liked alcohol, too, which earned her the additional nicknames of Slam Bang Sebastian, Slambastian or sometimes just Slam.

Rita Maenner, the creator of the Web site DorothySebastian.com, has devoted much of the past two years to researching the star. A longtime Hopalong Cassidy fan, Maenner was intrigued as she discovered details of Sebastian’s life. “My hope was that she wouldn’t be remembered as just Hopalong Cassidy’s fourth wife, Buster Keaton’s mistress or for whom she slept with, but as her own person with her own great acting abilities,” she said. “She had the drive, the talent and played with the big ones.”

Her dreams hadn’t come true easily, but with hard work and perseverance, Sebastian created her own luck. Tom Mix, a fellow film star, once said of her: “Don’t get the mistaken idea that Dorothy is a dare-devil, for she is not. But her success on the screen means more to her than anything else, so she does what she is told without whimpering. That’s why she’ll get somewhere before she’s through.”

Sebastian finished her career with nearly 65 movies, a lot to show for a little girl from Alabama who had wanted nothing more than to be a success on the silver screen. “Someday,” she had said in the early years, “I shall be a great star. That’s all that matters in life to me.”

(Background collected from DorothySebastian.com, 1926 Rose Bowl archives and clippings, imbd.com, b-westerns.com, rosebowllegends.org and alabamatv.org.)