by Danny Hanbery

As June 11 approached, the students at The University of Alabama felt tension in the air. They saw a police presence on campus that would turn into a National Guard presence as the swirl of events came to a head. Many of them helped to remove from the grounds anything that could be thrown to cause injury or incite a riot, just to be on the safe side. They read articles in the Crimson White about the two incoming students who were the cause for all of this preparation and were asked to obey several rules and a curfew set forth by the dean of men. Many of the students were frightened.

That was the summer of 1963.

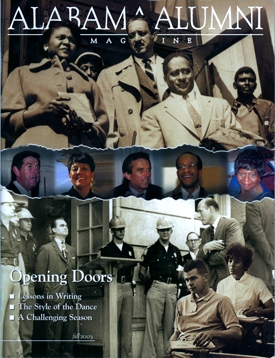

Forty years later, as June 11 approached, students felt no tension, unless they were in a particularly stressful summer class, though some of them might have felt a sense of celebration in the air. The University was again preparing for those two students to come onto campus. This time it wasn’t just the two, however. They were to be joined by others—students, administrators, priests and lawyers—who had also had a hand in changing the history of The University of Alabama.

This was the summer of 2003.

Vivian Malone, now Malone Jones, and James Hood came to the University under the gaze of the entire nation. Cameras recorded, reporters scribbled and Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace locked horns in a highly publicized political battle with President John F. Kennedy as two black students sought entrance to an institution that was part of the last segregated public school system in the country.

The University celebrated this integration with a program titled Opening Doors, June 9–11. The program served not only as an observation of that day, but also as a way to honor 40 people affiliated with UA who were pioneers in civil rights history. These individuals included Autherine Lucy Foster, who in 1956 was the first African-American to seek admission to the University, and whose admission caused riots on the Alabama campus, as well as Malone Jones and Hood. The rest of the pioneers were people who have broken color barriers or fought for equality in other ways, but the students who braved the social climates of the Old South and came to be the first African-American students at a previously all-white university top the list. Anyone who has been through an American history class knows why.

Almost everyone in the United States has heard about Wallace’s “stand in the schoolhouse door” through those classes, and even those who slept through class know about the events through cultural references such as in the movie Forrest Gump.

People from Alabama have heard about the incident for much of their lives because of the close proximity of the stage upon which the events took place, a stage that is joined by two other Alabama towns, Birmingham and Selma, in civil rights history.

But why should we look back upon this day in history as more significant than a hundred other important days? Or, taking the importance as a given, why revisit the events?

Dean Culpepper Clark of the UA College of Communication and Information Sciences, author of the book The Schoolhouse Door-Segregation’s Last Stand at The University of Alabama, explains the reason for the celebration this way: “At The University of Alabama we commemorate, even celebrate, because June 11, 1963, marked our liberation to become a whole university, one that could serve and be served by all people.”

As an integrated university 40 years later, students, faculty and alumni may not fully understand the meaning of that liberation without understanding the atmosphere on campus in 1963.

John L. Blackburn, who served as dean of men in 1963, impacted this campus in many ways during the years he spent here. The Blackburn Institute, which provides students opportunities to explore issues and identify strategic actions that will improve the quality of life for all of Alabama’s citizens, is named for him, and he is responsible for the creation of The Mallet Assembly, in which students who show leadership potential live in a self-governed environment. He is also being honored as one of the 40 pioneers and served on the “Opening Doors” planning committee. Blackburn came to the University after the riots surrounding Autherine Lucy’s admission in 1956. Initially, he had reservations about coming because he’d seen the images of violence in Tuscaloosa on television. He laughed when Louis Corson, who served as dean of men before Blackburn, called and asked him to come help out at UA. But Corson persuaded him by asking where else he would want to be if he wanted to help facilitate integration. On his first day at the University, Blackburn saw members of the Ku Klux Klan standing on the corners of what was then the student union building, now Reese Phifer Hall. They were there to prove they had the power to be there.

In 1958, Blackburn was appointed to his position of dean by UA President Frank Rose. He came to UA at the same time as coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, and Blackburn said all three of the men did their best to “reinstill faith and confidence in the institution.” That confidence could never have been in more danger than on the day of Wallace’s stand. The eyes of the world were on Tuscaloosa, and waiting to see something go wrong.

Blackburn was intimately involved in all aspects of the integration. He helped to prepare the students for the situation, he met with University leaders to plan the course of events and he tried to think of everything that might go wrong, and remove the threat. “In preparation for [June 11] we took out all of the bottled soft drink machines all over campus, picked up rocks and every piece of wood. There was nothing bigger than a toothpick you could find to throw,” Blackburn remembered, sitting in the office of Blackburn Educational Technologies, a firm he established after his retirement to “assist educational institutions and nonprofit groups in fundraising and long range planning.”

He and administrators, including Sarah Healy, the dean of women, chose 30 students to serve as leaders during the integration, to help smooth the transition. “These 30 students were really sticking their necks out because here they were coming out working to help integrate the University. If it went wrong and didn’t succeed . . . then their political careers were ruined, because political careers up until that time were based on being a segregationist,” Blackburn explained.

When it came time for that important moment in front of Foster Auditorium, Blackburn and the administrators kept as cool as possible, although they probably couldn’t help but sweat a little when Wallace initially turned Jones and Hood away from the door. The political maneuvering could have been explosive.

“I think Wallace assumed [Deputy Attorney General Nicholas] Katzenback would take the students back off campus, and then he viewed that they would have to have federal force to bring them back in. And so that would make the federal government the aggressor against the state,” Blackburn explained. “But when they were turned away by Wallace, we took them to their residence hall rooms . . . the inside of the campus, with the residence halls, was under control of the federal marshals. Now if Wallace was going to do anything, he would have to be the invader of the campus.” Fortunately, Wallace stepped down under Kennedy’s order federalizing the National Guard, and the school was successfully integrated.

“Prior to that date there was a cloud over the University. There were things you couldn’t do, there were meetings you couldn’t hold, because of that segregationist cloud,” Blackburn said. He described the day as exciting. “Most people don’t have an opportunity to live through an experience like that.”

It’s true that the combination of all of these events and experiences adds up to a moment of great historical significance. That in itself would be enough to celebrate Opening Doors–but that’s not all the organizers had in mind.

Samory Pruitt, UA’s assistant to the president for community and corporate relations, and chair of the planning committee for Opening Doors, shed some light on the reasoning behind the events. He said that the events today weren’t focusing on the fact that Wallace blocked the way of progress, but that progress prevailed. “At that point in the University’s history, it made a decision that everybody, regardless of race, should be afforded opportunities, and collectively the community, the students who were seeking admission, the federal government, they all agreed on that particular principle. That’s really what we’re trying to highlight,” Pruitt said.

In the end, the events at The University of Alabama on June 11, 1963, were important not only because of what did happen, but what could have happened. As it turned out, things went smoothly and Alabama became the last state to desegregate its public schools. The situation, however, included all the elements of a massive civil rights tragedy: men with guns, a Southern governor with a dedication to his constituency, a U.S. president who had to make things right, and two students entering a hostile environment with the goal of obtaining a degree from The University of Alabama. Five months later that president was shot on national television, 20 years later that governor renounced his segregationist past, and 40 years later we’re celebrating the events of that hot summer day, because it’s important to remember.

Times have changed since the days when an African-American couldn’t enter the University’s buildings for a glass of water, as reporter Chris McNair, a photographer for Ebony who was one of five African-American journalists covering Wallace’s “stand,” could not. Today UA is ranked among the top four flagship universities in the Southeast with regard to the number of African-American students it admits, and is ranked among the top 25 public flagship universities in the nation in the same category.

There’s still controversy over the lack of integration in UA’s greek system, but two new sororities are circumventing traditional greek boundaries on campus. Delta Xi Phi and Alpha Delta Sigma are both dedicated to issues of diversity. It’s a changed university.

This year also marks the election of the first African-American president-elect for the University’s National Alumni Association. André Taylor, who obtained his bachelor’s degree in journalism from UA 10 years after “the schoolhouse door,” is currently serving in that position. Reflecting on his position, Taylor said, “I think it is a very visible sign of the progress that has occurred over the past 40 years. Just simply the fact that I will be coming in as the head of the alumni organization says that opportunities exist today that clearly show the progress that has occurred at The University of Alabama.”

Taylor, whose two daughters graduated from the University and whose son is currently a senior, said that he believes the commemoration has been important to the school’s atmosphere and goals. “I think that the event really helps the University focus on the experience that African-American students have had and are currently having at the University, and then looks at ways to enhance that experience for future students.”

Opening Doors events included a symposium titled “Media and the Moment: Images of the Schoolhouse Door,” during which media professionals and those involved in “the stand” discussed the media coverage and politics surrounding the integration; a dinner program and gala, both honoring the 40 civil rights pioneers and featuring a speech by Robert Kennedy Jr.; the “Opening Doors Symposium: Reflections from African-American Alumni, 1956–2000,” during which African-American students from different decades discussed their experiences on campus; a community celebration on the Quad, highlighted by performances from musical and dance groups and ending with a candlelight vigil and procession to Foster Auditorium; and a culminating program at the doors of Foster with presentations by Gov. Bob Riley and Malone Jones.

June 11, 2003, was a hot and stormy day in Tuscaloosa. The sun shone just enough, however, for the celebrations on the Quad to continue as planned. People listened to singing groups while waiting for the candlelight vigil to begin. In the evening, the crowd gathered at Denny Chimes and lit candles, starting with UA President Robert E. Witt. Then, as dusk crept over the campus, the crowd with its glowing candles walked to Foster Auditorium, where they heard Malone Jones speak, standing in front of the door she had entered four decades earlier.

As she began, the wind picked up and the clouds overhead gave a subtle rumble. “I think God is sending me a message not to speak too long,” Malone Jones laughed. As she talked about that day when she came to the University in 1963, she interspersed her speech with the phrase “Indeed, what a difference 40 years has made.”

“Forty years ago what we saw when we looked out there—we saw bayonets, we saw the troops prepared for battle,” she remembered. Malone Jones said that on the UA campus she knew the meaning of the 23rd Psalm when it says, “Yea though I walk through the valley of he shadow of death.”

“Life was not safe in Tuscaloosa in 1963,” she said.

Her experiences steeled her for the road ahead when she would delve into politics and social change working with organizations like the Environmental Protection Agency. “I will serve my God, my country and my state by working to help our children to see my vision of a brighter day,” she said. “All of us have a right to worship, to be educated and to achieve the American dream.

“For over 130 years we as African-Americans could not have a legacy at this University,” Malone Jones noted, saying her children were the first generation of African-American children to be able to check the box on the application that says that their parents attended The University of Alabama. “Indeed, what a difference 40 years has made,” she observed.

Gov. Riley began his speech, but rain interrupted him as the storm finally broke. Fittingly, the entire crowd hurried together through the doors that had been closed to so many for so long, into the hot and dusty, but dry, Foster Auditorium, to finish the ceremony and hear the governor conclude by asking all Alabamians to embrace change.

To see descriptions and photos of the 40 pioneers honored during Opening Doors, visit the program’s Web site, at www.ua.edu/openingdoors.