by Danny Hanbery

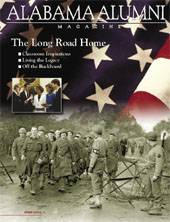

An unarmed Red Cross official crosses the German lines at St. Nazaire in Brittany, France, in 1944. His objective is to facilitate an exchange of prisoners of war, and to do this he must negotiate the unfamiliar French countryside, deal with Nazi officers whose language he does not speak and stand firm against their demands, all the while hoping the flag of peace he’s waving stops anyone from sending a bullet his way.

During the exchange he notices one of the prisoners, a British Special Air Services officer, is not among the soldiers he’s been sent to get. He asks where the man is, and the Germans indicate that he has tried to escape several times and is seriously injured. He knows too much, and will not be exchanged.

The Red Cross official will not accept this, and says the exchange is off unless all of the Allied soldiers he came for are released. Astounded, the Germans ask if he is willing to risk the lives of all the prisoners for one English officer. Yes, the official replies, he would risk it for one English officer, or one French private or any man among those counting on him—it’s all or none.

Sounds like a movie you’d like to see, right? Well, it did to Hobart Grooms, LLB ’54, JD ’55. He heard the story while serving as a trustee at Samford University and decided that a movie is exactly what this story called for. But he didn’t start searching for a screenwriter or a Hollywood producer; he just went to the source—Gerow Hodges, a fellow Samford trustee.

Hodges was that unarmed Red Cross official, risking his life to save Allied prisoners of war. Grooms also didn’t have trouble finding the English SAS officer in question. Michael Foot, whose life was saved due to Hodges’ stubborn resolve, went on to become a well-published historian, still writing at age 84, and was recently awarded the rank of commander of the British empire.

Foot came to Samford as a guest lecturer and had high tea with Grooms, Hodges and Dr. Tom Corts, Samford’s president, so contacting him was fairly simple. Grooms remembers sitting in on one of Foot’s WWII lectures, and described him as “an outstanding teacher.”

After piecing together the puzzle of information he had collected, Grooms knew he had found a story worth telling. “It was clearly unique. An unarmed, American Red Cross official, with only his wits and the little Red Cross badge, crossing into German territory. . . . There was no cease fire for most of the four exchanges. He just went in, waving that Red Cross flag, hoping no one would take a shot at him,” Grooms said. When he heard of Grooms’ passion on the subject, Corts asked to see his material. Seeing the same potential, Corts offered to locate a director and finance the film, and For One English Officer was born.

How did all of these events, the right people meeting at the right time, coincide to create a documentary? As Corts himself mused, “You’ve gotta either believe in coincidence or providence.”

There was a very good reason for Grooms, who by all accounts served as the impetus behind the project, to be interested in World War II. He was 10 years old when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, plunging the United States into the thick of war. “Birmingham industry made it a beehive of activity in the war effort,” recalled Grooms, who grew up in the Alabama city.

Common wisdom placed Birmingham, known as the “Steel City” because of its main industry, third on a list of German targets, right after Pittsburgh and New York, according to Allen Cronenberg’s book Forth to the Mighty Conflict: Alabama and World War II. This is the atmosphere in which Grooms grew up. While still in grammar school, he did his part to aid the war effort, selling war bonds door to door. “History was being made daily,” Grooms said. “At home, the war was the main topic at most meals.”

After graduating from The University of Alabama with a law degree and earning a major in history along the way, Grooms joined the Marines, serving as legal officer. Returning home, he practiced with the Birmingham firm Spain & Gillon, where he spent 41 years before retiring as a senior partner in 1999.

He never lost his passion for history, however, and when he heard Hodges’ story, he pressed the former Red Cross officer to let him see any documents concerning the exchanges. “That was really the hardest thing,” said Grooms, “getting to see what he had.” But eventually Hodges was swayed and presented Grooms with “a treasure trove of museum-quality documents.”

Grooms was amazed by what he saw. “Here were the original German POW lists, photos, correspondence, receipts for Red Cross parcels, cease fire agreements, even a 1938 Michelin map with an overlay showing coordinates where Hodges would meet the German officers who’d escort him blindfolded to enemy headquarters.” Hodges, who’d gone into the Red Cross instead of the Army because of a football injury that gave him a 4-F designation, crossed over enemy lines more than 15 times, freeing 149 Allied soldiers and airmen from prisons where some would surely have died before the war’s end.

With the story outline in hand, Samford’s funding and the help of award-winning director T.N. Mohan, based in Huntsville, Ala., who had previously completed documentaries on Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther, Grooms dove into the work.

He recalls compiling a “trial notebook, an attorney’s workbook containing documents and photos, which became an invaluable tool in preparing the documentary.” Hodges, who found it rather strange to think of his experiences as the basis for a film, said Grooms was “like a bulldog with the project.”

Grooms and director Mohan spent three days searching files at the National Archives and uncovering a lot of useful information, including Signal Corps photos and rare film clips about the exchanges. His 30-year career in the Marine Reserves gave Grooms a leg up in reviewing scores of military documents, dealing with veterans’ groups and communicating with military archivists overseas.

The lawyer drafted the script for the voice-over and mounted a search for the Americans involved in the exchanges, eventually locating 12 POWs in places ranging from Washington State to Georgia to New Jersey. He also located a French resistance fighter who had joined Foot in his escape attempts.

When the time came to hear the tale from the men who lived through it, Grooms calculated the cost of taking a film crew across the country to interview the POWs. The price of this journey was so great that Corts suggested a reunion of the American prisoners in Birmingham instead. Their stories were captured on film during a grueling two-day shoot. Some filming for the documentary also took place in England and France.

One of the toughest parts of making the documentary was deciding what to cut out, said Grooms. The film could be only 47 minutes long for screening on commercial television, and there was much more information there—such as the story of how Hodges was driving a German naval hero to German lines when he encountered what Grooms described as a “host of armed French resistance fighters, eager to settle old scores.” It took some time to convince the French that a prisoner exchange was involved, and the pair was allowed to proceed.

According to Hodges, Grooms gave “tremendous energy” for nearly three years to move the project to completion. To Grooms, “it was a labor of love.” He never thought he’d spend so much time on something so rewarding, he added.

For One English Officer caught the attention of Alabama Public Television, which aired it twice in January 2004, and it was offered nationally by PBS on Memorial Day. It was one of the film/video winners of the 24th annual Telly Awards, received a Silver Award from Omni Intermedia and was recently awarded the George Washington Honor Medal by the Freedom Foundation. It is currently being marketed in Europe and was shown during a D-Day observance in France.

“It’s a bit of history that would have been forgotten,” noted Grooms. “We lose 1,800 World War II veterans a day. The story had to be told.”

Copies of the video documentary For One English Officer can be purchased for $12 from the Samford University Bookstore by calling (205) 726-2834.

Danny Hanbery received his bachelor’s degree in journalism and English from UA in 2004, and works for Southern Progress as an online producer.