by Caroline Gwaltney

Walk into the Rise School on the University of Alabama campus and you are instantly greeted by a foyer boasting beautiful portrait paintings that commemorate the program’s history.

Continue further down the hallway and you’ll find an enormous common play area for children along with several jungle-gym sets. The 1-year-olds are enjoying music time, their doll-sized hands clapping as the teacher plays the guitar. The 2-year-olds, rubbing their eyes, are quick to get up from naptime and excitedly await their next activity. Artwork of dinosaurs, zoo animals and colored drawings of the children’s families adorn the walls of the state-of-the-art building.

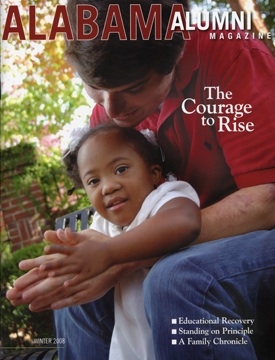

Look around more closely, and you’ll realize what you’ve found is a uniquely blended community filled with children who have disabilities, as well as their typically developing peers—although the kids can’t seem to tell the difference.

The setting may seem extraordinary now, but it has not always been the preschool with idyllic qualities.

Just ask Dr. Martha Cook, who 34 years ago became the first teacher of Rise, with six students in a single room of a house on the UA campus, part of one of the first early intervention programs to serve young children with disabilities. Since that time, Cook, now the director, has helped transform Rise into a nationally recognized model for the development of similar programs all over the country.

After Cook, along with a teaching assistant and a family service coordinator, helped get the project off the ground with federal funding, The University of Alabama added its support, and the facility expanded to include three classrooms. By 1978, Rise had moved to Wilson Hall, a converted women’s dormitory, which it would call home for 16 years. A dark, dreary building at the time, the location posed many challenges, especially the narrow hallways that weren’t wide enough for wheelchairs, according to Cook. “It was totally inappropriate for a children’s program,” she said. “None of the fixtures had been changed, and there was absolutely no space.”

But Cook, whose positive attitude and will to persevere are likely unmatched, continued with the program, hopeful that it would one day be a thriving place with unlimited opportunities. “I didn’t leave because I did think it was the ideal job,” Cook said. “It was a program based on hope, and we just kept hoping that we would make it to the next year.”

The year 1986 brought about sweeping changes as Rise drastically transformed its curriculum by mixing children with disabilities with mainstream children. The concept was that through their interactions the mainstreamed children would blossom into thriving individuals with leadership qualities and high character.

“Our initial thought was that bringing in mainstream children would allow the children with disabilities to interact and learn from them, which we’ve found to be true,” Cook said. “But in reality, the mainstream kids can learn just as much from the children with disabilities.” The program also expanded in its relationship to the rest of the campus, becoming a source of teaching and research opportunities.

But perhaps the most important year for the program was 1990, when Gene Stallings was hired as head football coach for the Crimson Tide, and immediately became an enthusiastic advocate for Rise. It was a cause near to his heart—his son, Johnny, had been born with Down syndrome. By 1992, the year Stallings’ team won a national championship, the University began a capital campaign that included a new facility for the Rise School. And the dream became a reality on Nov. 30, 1994, with the opening of the Stallings Center. “It was just the greatest day on earth,” Cook recalled.

You could say the rest is history. There are now six classrooms capable of serving 80 children. A staff of nearly 40 is on board, bringing with it an overwhelming national prominence.

Franny Jones, the assistant director of Rise, was instantly struck by its unique approach when she was a student at UA working at the center. She found her experience to be a new way to look at life. “I love that everyone gets to be the line-leader, even if they can’t walk and are in a wheelchair,” she said.

Rise primarily accommodates children with Down syndrome, spina bifida and cerebral palsy. Jones said one of the best aspects of her work is experiencing the daily miracles and victories. “We hear doctors say someone’s never going to be able to do this, but we honestly don’t know what that means around here,” she said.

Another interesting aspect about Rise is that its alumni can’t seem to stay away; many return to volunteer or teach.

Jake Craft, a junior special education major at the University, is a Rise graduate who has volunteered since he was 16, and is now employed as a student worker. “It seems like whatever I do, all roads lead to here,” he said. Craft began attending Rise when he was 3 months old, and said his first memory of the experience was getting to trick-or-treat in Coach Stallings’ office. Born with cerebral palsy and later suffering severe burns in a house fire, Craft said he felt like he owed a lot to the program. “I definitely wouldn’t be where I am without Rise,” he said.

A former classmate of Craft’s, Kayla Terry also has fond memories of her time at Rise. Terry’s older brother, Ian, who has Down syndrome, was already a student there when she became one of the first mainstream participants to attend in 1989, at just a few months old. Acceptance, tolerance and helpfulness all became qualities that were as automatic as breathing for Terry. She realized at an early age that everyone was different, and attending Rise gave her an appreciation for not just accepting those differences, but celebrating them, she said. “I was the one who wanted Santa to bring me a wheelchair because I thought it was a neat way to get around,” she added.

As a senior in high school, Kayla wrote a biography about her brother for a class project. She first distributed several copies to family members, but then got more and more calls from other people who wanted to read Ian’s story. Now a junior at UA, she has turned the memoir into a self-published book, An Every Day Inspiration: The Authorized Biography of Ian Terry, which is available at Amazon.com. Ian, also a graduate of Rise, is now employed by the program. “Ian’s motto is ‘dare to dream,'” Kayla said. “He wants people to see that you can have ambition, even if people think you can’t do it.”

As for the future of the Rise preschool, Cook hopes to see it grow and continue to be a source of innovation for these types of programs across the country. And who knows, she said, maybe there will be a Rise elementary school one day.