by Katharine S. Crawford

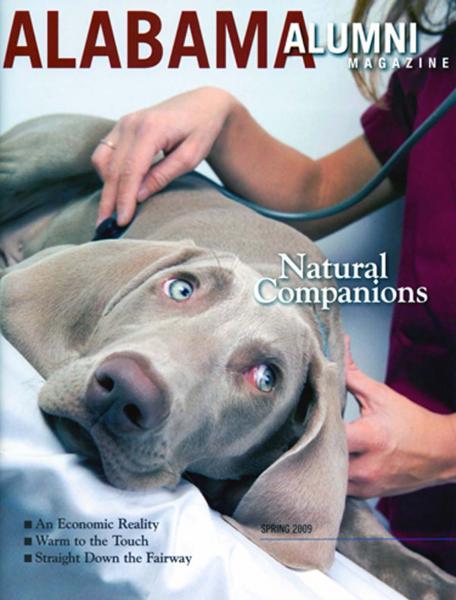

Many wear collars, others saddles. Some have paws, some claws. While they sometimes tug on our pant legs, they more often pull at our heartstrings. The connection between man and his pets reaches back through the ages, and runs as deep as the soul. And for some of The University of Alabama’s own, the human-animal bond is not just a personal connection, but a calling.

Eager to Learn

When Laura Catharine (McDaris) Brittain enters veterinary school this fall, she won’t only pursue a degree, but also the fulfillment that comes from doing something she loves. A 1999 UA graduate with a marketing degree, Brittain said she always felt challenged in the various jobs she held. Six years out of college, however, she realized “pursuing a career you love, even if later in life, is preferable to looking back and wishing you had done something else.”

After going back to school—she earned science prerequisites from The University of Alabama at Birmingham—and working as a veterinary technician in Birmingham, Ala., Brittain is set to attend one of the five vet schools to which she has applied. Although her career path has turned, she will incorporate what she learned at the University in her medical training and her career, she said. “The business school prepared me for the world; I just needed some time to find my place in it,” she explained. “With the practical experience I accrued, I feel well prepared for clinic administration.”

Brittain, who was born in Germany but raised in Tennessee, said she dreamed of being a vet as a child. “Companion animals have become family members to many people. Owners are also closer to their veterinarians than in years past, and animal medicine has become every bit as sophisticated as medicine for humans,” she pointed out.

“The administrative side of the clinic is advancing as well. Software has been developed to manage appointment scheduling, medical records and inventory. In fact, the clinic at which I work has gone paperless. Our reminders for vaccines, routine dentals and checkups are now sent via email.”

As a vet tech, Brittain does everything from drawing blood to assisting in surgery. When she isn’t working, she finds time to volunteer at the Birmingham Zoo, where she aids zookeepers with zebras, giraffes and ostriches, to name a few. She and her husband, Lee, have three dogs. Emmy, their 9-month-old yellow Labrador retriever, is the first puppy Brittain delivered, and happens to be the daughter of their black Lab, Mac. Mills is the couple’s beagle.

“I have learned that on any given day, a veterinarian acts as a friend, an emergency room doctor, a facilitator of preventive care and sometimes a grief counselor,” she said. Her favorite moments are watching the recovery of a critical-care patient. “As the animal starts feeling better, you can see a change in its eyes.”

Ready to Serve

Large or small, domestic or undomesticated—Banks Douglass has treated them all. During his four years as a student in Auburn University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, his education has included work on household pets, mostly dogs and cats; farm animals like cows and goats; and even such rarities as llamas and alpacas.

A native of Lexington, Ky., Douglass has plans to move to Ocala, Fla., after receiving his doctorate of veterinary medicine in May 2009. Both Lexington and Ocala claim to be the Horse Capital of the World, which is only fitting for Douglass. Familiarity with the animal will help him in his next venture: working exclusively with horses in a year-long internship at Equine Medical Center of Ocala.

Still, it was a childhood incident involving the family dog that drove Douglass’ decision to become a vet. “Our pet yellow Lab, Lilly, was hit by a car and broke her leg when I was young,” he recalled. “Seeing how much her vets cared for her and helped her recover strengthened my desire to become a veterinarian.”

A 2004 graduate of UA with a degree in biology, Douglass says it “just made sense” to go into animal care. For many, including Douglass, pets count as family members. “Veterinary medicine has changed a lot recently in that pets are an extension of a human family, and they should be treated as such,” he said. “It makes our jobs easy when clients want the best for their animals and will seek whatever care is necessary.”

“There is a shortage of veterinarians in many parts of our country,” Douglass said, adding that students should pursue veterinary medicine degrees because “it is so rewarding.” The greatest returns, he said, are when sick and hurt animals, like Lilly, become healthy through his assistance. To this day, he keeps a yellow Lab around for company—a 2-year-old male named Chief.

“Pets and all animals are such a large part of our lives, and in many instances people don’t realize what significant roles they play,” he said. “Whether they are companions and friends, those that provide work or even producers of our food, animals are very important. It is enjoyable to play an integral role in it all.”

Leaving a Mark

Not many people have helped inoculate a rhinoceros, but for Dr. Erin Akin, such unusual experiences are, in fact, the usual. Take, for example, the time she spent in South Africa as a vet student, where she studied exotic animals at a game reserve. Four years later, as a first-year veterinary neurology and neurosurgery resident at Auburn, every day still presents new challenges. “I am often on call 24 hours. Recently, I performed an emergency back surgery at midnight,” she says.

After receiving a chemical engineering degree from the Capstone in 1998, Akin worked for five years as an engineer. She chose to attend the University because of its “reputation as a top-notch engineering school” and was the 1993 Vulcan Scholar. “At UA, I worked hard and learned the critical and analytical thinking skills needed as an engineer and, as it turns out, a veterinarian,” she said. “My favorite memories of school revolve around my involvement in Theta Tau, the professional engineering fraternity, and I fondly remember taking my dog for walks around the Quad.”

Now the owner of three dachshunds—a female, Chloe, and two males, Casey and Oscar—Akin said, “Most people are surprised when I tell them I went from engineering to vet school. There was no specific event that made me want to change careers—more of just a gut feeling.” She has called Alabama home since 1988, and said her parents, who live in Seoul, South Korea, have been “phenomenally supportive” of the career change.

Having earned her doctorate, Akin’s next move is to become a veterinary neurologist and neurosurgeon upon completing her residency in 2011. She is also working toward a master’s in biomedical sciences.

“For almost any specialty in human medicine, there is a counterpart in veterinary medicine,” Akin explained. To become a specialist, she will undergo three-plus years of advanced training, and then must pass certification exams. “There is a huge variety of care I perform as a resident, including spinal surgery, brain surgery, and muscle and nerve biopsies. Pets present to me for anything from seizures to having a weakness in their rear legs.”

Her favorite condition to diagnose and treat is intervertebral disc disease, similar to herniated discs in humans, which many animals overcome with surgical intervention. “I love all my patients,” Akin shared. “The most rewarding part of what I do is making a difference in the lives of patients and their families.”

A Career in Caring

Dr. Robert Shamblin is a vet in every sense of the word. His D.V.M. may make him a bona fide veterinarian, but 37 years of practicing animal medicine make him a true veteran. Even so, Shamblin would be the first to admit he’s still learning.

A 1968 University of Alabama graduate with a bachelor’s in history, Shamblin said, “I wasn’t spoon-fed at UA. Professors gave students the skills to continue learning, to be creative and teach ourselves.” He recalled history courses with Dr. Sarah Wiggins, who, along with her cocker spaniel, Bob, is now a client of Shamblin.

Though his current practice deals primarily with cats and dogs, Shamblin worked daily with large animals growing up on his family’s farm in Northport, Ala. The farm, where he lives to this day, is home to two dogs, Gypsy and Freckles; two cats, Maggie and Willie; and horses Tennessee and Montana. “Horses are to cats as cows are to dogs,” Shamblin explained. “You have to out-finesse a horse as you do a cat, while cows and dogs will generally submit to treatment and medicine.”

Shamblin said that the industry has seen notable changes since his graduation from Auburn’s vet school in 1972. “The human-animal bond and pet owner responsibility have grown,” he said. “Microchips are commonly used in large animal sales, and in the future, global positioning will make their use more beneficial for domestic pet owners.” About the advent of pet medical insurance, Shamblin says, “It hasn’t really latched on in the Southeast, but it is a good thing to have—as long as one researches the many policies out there before obtaining one.”

According to Shamblin, “A vet’s job is to help the animal that can’t help itself.” He recalled the time a boa constrictor escaped in his clinic and got its head stuck in the waiting room toilet. On another occasion, he removed a hunting arrow that had narrowly missed a dog’s aorta. Both cases ended in full recoveries.

Shamblin insists, however, that he isn’t a healer. “I just get conditions right so the animal’s body can heal on its own.” He said his best days are helping patients come through illness, and the routines—checkups, vaccinations and dentals—are also enjoyable. “It is challenging to see a patient that can’t get well, that you’ve grown to love but can’t help,” he said. “Still, I keep seeing reactions that I’ve never seen before—new things that confound and humble me.”

Katharine S. Crawford, ’07, is public relations and publications manager for the Alabama Humanities Foundation.