Through Special Collections’ crowdsourcing programs, photos can be identified and handwriting deciphered with the help of anyone and everyone.

by Haley Grogan

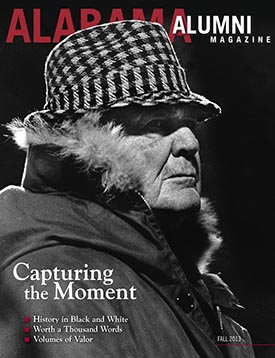

Sometimes it seems that the history of The University of Alabama can be told in black and white—in newspaper headlines, in faded Polaroids, in the pattern of a hat. While the years have rolled on, pieces of that history have stayed, in images left behind: soldiers in training, civil rights milestones and last-minute sports victories. But in our hurry to grow with the times and start telling our story in color, there were parts overlooked. The UA Libraries Division of Special Collections is working to recapture those memories through digitization and identification of vintage photos and memorabilia.

The UA Libraries’ collections are home to a hundred thousand blurred faces and twice as many dark eyes, peering at the camera through grainy film and dust specks. The decades have stolen their names, sometimes leaving only fragments of descriptions behind: football player, unidentified man, student with analog computer. Sometimes the passing time left no information at all. Countless documents and letters, wrinkled and creased from long years in envelopes and with outdated cursive handwriting swooping across the yellowed pages, are filed away in boxes.

Though they are a treasure of information for genealogists, historians and researchers from many different fields, the puzzles left in these photos and documents could take a lifetime to solve, such as “Who is in this photo?” or “What Civil War battle does this diary mention?” For answers, the Division of Special Collections has turned to crowdsourcing, a computer-based process that allows many people to combine their efforts, working at their own pace, to solve a time-consuming and difficult problem.

One of the Libraries’ biggest crowdsourcing endeavors is the “Tag It” project, which allows users to add valuable information to online photograph collections by tagging photographs and identifying people, places and things that were not recorded when the image was collected and not available when it was digitized. “Since it’s online, users anywhere in the world can look at the photo and put in even one simple word that describes what the photo is,” said Donnelly Walton, the archival access coordinator with Special Collections. “It’s an opportunity for us to gather that information.”

Jason Battles, associate dean for library technology planning and policy, said that “Tag It” is more than just identifying people in the photos. “Perhaps someone can identify a time period by noticing the type of automobile or building in the picture. For example, the user could share that a photo dated 1963 actually had to be later than that, because a building in the picture wasn’t built until 1969.” The tags that users provide will be added to Acumen, UA Libraries’ digital repository that allows anyone interested to search collections. The more people, places and things that users tag, the richer the experience for all.

As an extension of the “Tag It” project, Special Collections is joining with UA’s branch of the Army ROTC to digitize more than 20 oversized scrapbooks, dating from 1953 through the late 1970s.

Mary Bess Paluzzi, associate dean for special collections with the UA Libraries, said the project was prompted by a visit in September 2012 with Lt. Col. Kenneth Kemmerly, Signal Corps, who is commander and professor of military science for UA’s Army ROTC. He showed her the ROTC’s collection of scrapbooks, and she noticed several of the albums were in poor condition. “Some of the books weren’t in really good shape,” Paluzzi said, “so we began to talk about the possibility of him letting us digitize them.”

Military training on UA’s campus goes back to before the Civil War, when the campus was used as a cadet training base. Kemmerly said that part of the reason he wanted Special Collections to take charge of the scrapbooks is because it’s important to honor the heritage and the history that military service has with UA. “The presence of military training on campus goes back to 1860,” he said. “There is a long history, and you have so many alumni, some extremely famous, like Winston Groom.” Groom, the author of Forrest Gump and other books, some focusing on military history, was in the Army ROTC before graduating in 1965 and serving in Vietnam from 1965 to 1969. “Many people went into the program and acquired skills, and became better citizens,” Kemmerly noted.

The scrapbooks had been kept in the Duco Library, the Army ROTC Cadet Military Science’s library room, in the old U.S. Bureau of Mines building on campus, which sits just off the Quad and houses the ROTC program. Kemmerly said he knew the scrapbooks would be a hit with the many program alumni who stop by the building during the school year, particularly during football season. “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if they were digitized or available online so children and grandchildren could see their parents or grandparents?’”

When the project is complete, Kemmerly will have a disk of the digitized versions for easy access, and the books will stay housed in Special Collections. “I didn’t want these books to be lost,” he said. “I wanted them to be accessible to alumni and their children. And when folks start coming in, I will show them what we have digitized, instead of reopening the books. They need to be with historians and people who know how to preserve those types of artifacts.”

Paluzzi said that the staff of Special Collections, along with the Cataloging and Metadata Services and Digital Services departments, has been hard at work, because the process employed with the “Tag It” and ROTC scrapbooks projects is extensive. UA Libraries plans to use the scrapbooking project to create a basis for similar projects in the future. “We’ve never had something this size,” she said. “There are around four to 10 items per page. We had to set priorities and procedures.”

It’s not just the scanning of such large volumes of photos that’s challenging, she explained, but identifying what is happening in them—and that’s where crowdsourcing can help. Large portions of the scrapbooks have few descriptions, though several photos have been identified so far, including one where Dr. David Mathews, the University’s president from 1969 to 1980, received his Army commission. Other famous faces have also been recognized: One photo features Joe Espy, a 1969 graduate and current member of UA’s Board of Trustees. Another shows Sandy Kirby Witt, wife of UA System Chancellor Robert E. Witt, when she was a sponsor of an ROTC company in the late 1960s. The sponsors of that era were women students chosen to march as part of the corps during campus events.

One of the best things about the scrapbooks is that they illustrate the change of the Corps of Cadets over the years, Paluzzi said. “After 1963, you can see the desegregation of the University, and into the 1970s you can see women coming into the corps,” she observed. “If you look at the photos from the 1950s, there is no person of color at all in the ROTC. These books captured cultural changes, not just at UA, but through the course of the nation’s history.

“So many of the young faces in the 1960 scrapbooks made the ultimate sacrifice for their country while in Vietnam. These photos capture the youth of the Alabama Corps of Cadets.”

In addition to the “Tag It” venture, Special Collections has also initiated the “Transcription” project, which allows users to help decipher scanned documents and update their descriptions. Handwriting, especially from the 19th century or earlier, can be difficult to read for eyes accustomed to crisp, black font on backlit screens. By entering the “Transcription” database, users can take some time to study the characteristics of a writer’s style in order to translate the text of a manuscript, then add valuable information by recording their conclusions.

The process of transcribing old documents and letters can be time-consuming, so having help from the community is important, according to Donnelly Walton, archival access coordinator for Special Collections. “It’s a lot of fun for people who like to do that stuff, like me,” she said, “but it is a very labor-intensive task that we just cannot do alone. If other people in the community want to do it for us, that’s extremely helpful.”

Additionally, these transcriptions support full-text keyboard searching, which is invaluable to researchers. “The original documents can’t be keyword searched,” Battles said. “The researcher would have to read through an entire letter or diary looking for information. But with the full-text keyword search in the transcription, researchers can know immediately which documents are relevant. It saves countless hours.”

Much of the material housed in Special Collections relates to the history of UA and the city of Tuscaloosa, and Walton said it’s important to maintain the background of the places we call home. She added that the “Tag It,” “Transcription” and scrapbook projects are representative of the changing perspective of archivists: It’s important to give the information back to the community, rather than hide it away. “There was a different time where archivists were more guardians of the information, and very protective,” she said. “Now that’s reversed, and we want other people to use it. It’s not ours; it belongs to the University, and the community.”

To try your luck at tagging or transcribing, go to tagit.lib.ua.edu or transcribe.lib.ua.edu. The ROTC scrapbooks are available for viewing by the public on Acumen, the libraries’ digital collection, at acumen.lib.ua.edu.