A collaboration on Shakespeare becomes an ongoing cultural exchange.

by Lauren Cabral

The emotions evoked by art are something we all have in common, regardless of the medium. This shared experience can foster communication between people from different backgrounds, and even overcome barriers. In one good example at The University of Alabama, the medium is theatre, and the boundaries that have been transcended are language, culture, politics and the Gulf of Mexico.

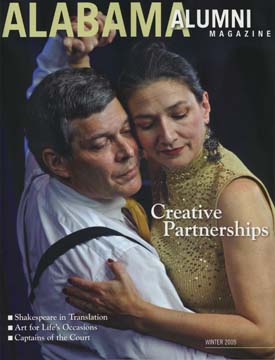

A unique collaboration between the University and Cuba exists in the form of the Cuba-Alabama Academic Initiative, and within it, assistant professor of acting Seth Panitch has done something unprecedented. The UA faculty member became the first American to direct a play in Cuba since the Cuban Revolution of the 1950s launched Fidel Castro into power.

His graduate students joined the theatre division of Consejo Nacional de las Artes Escénicas (CNAE), the Cuban ministry of culture in charge of performing arts, to produce two of Shakespeare’s works. The first, The Merchant of Venice, was performed in Havana, Cuba, in December 2008, and the second,A Midsummer Night’s Dream En Español, took place at the Capstone in August 2009.

The significance of this collaboration is paramount, and nobody knows that more than Panitch. “To be first at something, anything, is very special,” the accomplished director said. “Why put your blood, sweat and tears into something that’s already been done?” That valid question only highlights the significance of what Panitch and his students have accomplished. Not only did they successfully put on a production in a language they don’t speak and in a country that is almost forbidden for travel, but they brought two very different cultures together through art.

“In theater, there are very few firsts,” Panitch said. “I wanted to be able to be a part of something that was new—and this was pretty much as new as I could get.”

The Creative Process

Panitch’s involvement with Cuba began in 2005, when he started researching its acting styles. He first went to the country in December 2006, on an invitation from Dr. Robert Olin, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, along with representatives from various other departments. Although most people don’t have the option to visit Cuba because of travel restrictions (our government will only allow travel there for specific reasons, such as family visits and educational or humanitarian efforts), in 2002, UA had received academic travel licenses from the U.S. Department of the Treasury for academic activities as part of the Cuba-Alabama Initiative. The licenses also provided opportunities for UA to invite Cuban scholars to its campus.

It was in this semi-banned land that Panitch made a connection with the Instituto Superior De Arte (ISA) in Havana, an art training program. The school is known for having the highest-quality actors in the country, and Panitch was thrilled when the chair of the theatre department invited him to work with students there.

“Dean Olin is always saying, ‘Well that’s good, but what’s next?’” said Panitch. “I wanted to expand upon that.” He did just that when he managed to get the go-ahead for six of his students to fly with him to Havana. When they arrived, they were a bit stunned, to say the least. Panitch described their look as one of a deer in the headlights, which is understandable since they did not speak Spanish and were in a completely foreign environment. “No matter what I’d prepared them for, it just didn’t match up to what the reality was,” he said. “This was a growing experience they needed, though.”

Panitch said many of his students had never left the country before, and he had encouraged them to get outside of their comfort zone. “I’m always trying to teach them about the human condition, not the American condition. And to learn that you have to experience more than the Southeastern Theatre Conference.”

Jeremy Cox was one such graduate student. He accompanied Panitch first to observe classes at ISA, and again to participate in the Merchant project. “The Cuban trips were my first time to be outside of the United States, but there was something that still felt like home, something familiar, or perhaps seeing the passion that drives my cast mates,” he said. “Cuba has to be certainly the greatest experience in my acting career thus far and ranks high in life experiences—the chance to enter another world and observe the similarities and differences, and embracing that as part of the experience.”

As for the Cuban actors, they had to adjust to the fast pace of the Americans. Instead of rehearsing for a year before putting on a show, the normal practice in Cuba, Panitch aimed to rehearse for five weeks, which the Cubans didn’t believe at first. In fact, when he told them he’d block the play in one week, meaning to determine all placements and movements of the actors on stage, they laughed. “Cuban directors don’t prepare the same way American directors do,” Panitch explained.

Erich Cartaya, Cuba’s international events and programs specialist who served as the coordinator between CNAE and UA, said he believes the Cubans adjusted well to the new production schedule despite their youth and the difference in their educational backgrounds. “I think this was one of the greatest achievements of the exchange,” he said.

As rehearsals for Merchant progressed, the group experienced some setbacks. Of the 12 Cuban actors cast, only three ended up in their original roles. About half of the group dropped out of the production due to family hardships and deaths. “It’s a different life in Havana; it’s not easy,” Panitch said. “Working in Cuba is an immense challenge because of the poverty of people.” Despite these hurdles, one thing did make things much easier: the Cubans’ passion for their work. One actor told Panitch he turned down two soap opera jobs because he wanted to work with an American director and perform Shakespeare.

Cox also noticed the commitment of his Cuban counterparts when, after showing a few exercises to a class of actors, they were eager to try them. “That was something that I admired—the great passion and desire to be educated,” Cox said. “Although there was a language barrier, being that I speak very little Spanish, I felt that we were all on the same page in that classroom.”

It was the language barrier that influenced Panitch to choose Merchant, and later A Midsummer Night’s Dream. “I was confident that I could do it in Spanish and understand what’s going on.” The students did as well, he said, and the Americans performed their Spanish lines well with help from their newfound friends.

The World Stage

The play ran from Dec. 17, 2008, to Jan. 4, 2009, and had several sold-out evenings. The venue was the Sala Teatro Adolfo Llauradò in Havana, which Panitch chose because it was the only available theater without a hole in floor.

Tom Wolfe, associate dean of humanities and fine arts and professor of jazz studies at UA, composed and performed the music for the play, which was mostly classical guitar. Wolfe said the opportunity to be a part of the project was one he couldn’t pass up. “For years, we’ve wanted the opportunity to come together and create art that has not been done, that we know of, in this type of collaboration,” he said. “Everyone learned so much in this project. It was a great opportunity for both the Cuban students and our own students.”

As for Panitch, he said he did not relax until the second night. “I was sitting there in the back of the theatre watching Cubans respond to a 400-year-old piece that was being directed by an American and being performed by professional Cuban actors and American student actors in Spanish, and I realized that we were making history,” Panitch said. “I looked at the results of four years of work and was amazed, because I never thought it could get to this level.”

Merchant received a great deal of coverage in Cuba and the international press, and the feedback was extremely positive. “To work with a professional of Seth’s caliber is enriching; he taught us to know Shakespeare,” Cartaya said. “The Cuban public had not had the opportunity to see The Merchant of Veniceon stage, and after seeing the performance, theatre directors were stimulated to put on works of this important playwright, such as Macbeth and Hamlet.”

It makes sense, then, that Panitch decided to try a similar collaboration on U.S. soil. Not even a year later, he directed A Midsummer Night’s Dream En Español right here at UA. Twelve actors from the CNAE teamed with nine UA theatre students to put on the play, which ran from Aug. 6 to 8, 2009, at the Allen Bales Theatre. Cartaya again served as coordinator, as well as stage production manager, and Wolfe again composed the music, which this time was psychedelic and rock-themed, featuring music in the styles of Jimmy Hendrix and other 1960s artists. John Virciglio, dance choreographer and instructor; Donna Meester, costume designer and associate professor of theatre; and Rick Miller, set designer and assistant professor of theatre, also helped with the production.

Although the response was similar—applause, media attention and praise—the process was much different. “I could control rehearsals. I knew where the Cubans were,” he said. In Cuba, delays had occurred due to broken down cars and various crises that needed attention. Here, there was none of that, and as a result, rehearsals took two weeks, said Panitch, “Even though the Cubans had a hard time focusing because they wanted to see everything.”

A Better Understanding

Sitting in his office in Rowand-Johnson Hall, Panitch paused when asked for his most vivid memory of Cuba. He then began describing an afternoon at a café, where he sat next to a four-way intersection, watching people go by. “There was always music. People always seemed to be walking to music,” he said. “Everyone was touching each other; there was such a compassion for their fellow people. I realized that this was a beautiful culture, and I wanted to understand it better.”

And that understanding has taken root. After his two projects with Cuban actors, Panitch said he will never forget their unique qualities. “There’s something dynamic about Cubans that no other culture has, and I wonder if it’s partly because they’ve been so isolated on the island,” he said. “They had a distilled vitality that is unlike anything I had previously encountered.”

Considering the success of both plays, more collaborations are possible, according to Panitch. “I think that this project has been successful enough that the University is willing to support that.” And ISA has asked him to come again. “It’s pretty much an open door,” he said, but acknowledges it would be easy to keep putting it off, something he does not want to happen.

“The danger in these programs is we’re going to get so caught up here we’re not going to continue there, and we’re going to lose it.” He is well aware of that danger, and wants to prevent it from becoming a reality. There has been talk of May 2010 being a good time for another collaborative project, and though there are no specific plans mapped out, Panitch is confident there will be.

Cartaya mentioned that politics may still impose barriers on the program, but that impact might not be as harsh in the future. “This project served to open a communication bridge between the U.S. and Cuba, and as always, culture overcomes the politics of the moment,” he said.

“I think that as times change and it becomes easier for us to have these relationships, the departments and universities that already have these relations are going to be at a great advantage, because we have been able to build up a level of trust,” Panitch pointed out. “And in Cuba, trust is so important, especially when it comes to dealing with the U.S.”

Regardless of the future, the outcome of the two Shakespeare projects was something nobody involved will ever forget. As Wolfe put it, “It’s just fulfilling to be able to bring something about that we know students are going to look back on for the rest of their lives as a fond experience that, frankly, nobody has ever had.”

(Quotes by Erich Cartaya were translated from Spanish by Lauren Cabral, with assistance from Miguel A. Gutierrez and Mari E. Gutierrez.)

To receive four issues of the Alabama Alumni Magazine each year, Join the Alabama Alumni Association Online