After taking off in the early days of flight, the University’s aviation school prepared pilots for battle.

by Caroline Gwaltney

Take a glimpse into 1930s America and you’ll see a bleak picture of a country weathering the economic storm of the Great Depression, marked by declines in the production and sale of goods along with a severe rise in unemployment.

But in the world of aviation, these were the glory days—a time of excitement that brought a new, thrilling aspect to life and culture. In 1927, Charles Lindbergh had crossed the Atlantic and returned to New York City, where he was greeted by the largest crowd ever to assemble there. A few years later, Amelia Earhart became the first woman to accomplish the same feat.

It was the decade that saw the implementation of air-mail service across the Atlantic, Boeing Air Transport introduce the first female flight attendants and Lindbergh use his fame to relentlessly promote the rapid development of U.S. commercial aviation.

On the University of Alabama campus, the engineering school responded to the growing interest in aviation by officially beginning a new program of study in 1932. Soon it would become one of the College of Engineering’s greatest contributions to the country, not only in technological development, but in training of military personnel.

Its first effort was a flight instruction program initiated by the aeronautical engineering department. The University and the city of Tuscaloosa had cooperated on building an airport in the late 1930s. According to Robert Norrell, author of A Promising Field, that facility had enabled the school to start one of the first collegiate civil pilot training programs in the country, and its early success with that venture made the engineering college ready for full-fledged military flight training by the time World War II was on the horizon.

The aeronautical engineering program was lifted off the ground with the help of Dr. Fred Maxwell, a member of the first graduating class in mechanical engineering at the University. An experienced Navy pilot and an electrical engineering professor, Maxwell had been involved with teaching a class in navigation since 1929. “Fred Maxwell was truly a Renaissance man,” said Dr. Chuck Karr, current dean of the College of Engineering and professor of aerospace engineering. “He climbed to the top in everything he did.” Maxwell was initiated into the Alabama Aviation Hall of Fame in 1985 and was recognized by the U.S. Navy as the oldest living Navy pilot in the country in 1986. He passed away in 1988 at the age of 99.

Despite the aeronautical engineering degree not yet being official, 59 students had already signed up for the class in 1931. By 1933, the program had grown to 165 students and a single airplane was available for study.

Leslie A. Walker, a 1915 graduate of UA and a Navy pilot, directed the teaching duties during the early years, when courses were largely limited to airplane maintenance, aerodynamics and meteorology. It wasn’t until 1936 that Otto H. Lunde helped expand the curriculum to include advanced courses in aerodynamics, aircraft engines and aircraft design.

In 1938, a senior student in aeronautical engineering developed a design for a low-speed wind tunnel built of wood. This equipment continues to be used to this day. In fact, it serves as a focal point of tours when alumni visit the campus because virtually every graduate of the program has had the opportunity to run tests in this facility. Edward Finnell, its designer, was a 1938 graduate and later became a student recruiter for the College of Engineering, serving in that capacity until his retirement.

The aeronautical engineering department made great strides in the late 1930s, becoming one of nine programs in the country to be fully accredited by the Engineering Council for Professional Development. UA was also one of 13 institutions in the nation selected by the Civilian Aeronautics Authority (the precursor to the Federal Aviation Authority) to conduct its experimental civilian pilot training program.

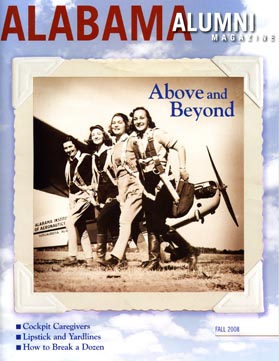

The original purpose of the program, which began in 1939, was to aid in the proper instruction of private flyers, but after World War II began, the emphasis became preparing young men and women for military flying. “A lot of people didn’t realize what an integral part our aeronautical engineering training had in preparing soldiers for the war,” Karr said, “but the University was leading these types of programs.”

The aeronautical professors stepped up the pace of the training effort in 1940, taking in more than 200 future pilots. They also gave instruction to ground crews. Walker, who was called upon by the Civil Aeronautics Authority to help start similar programs at other universities, was replaced by Colgan Bryan, who had taught civilian pilots in Virginia.

Bryan came to UA in 1942 to teach and coordinate a World War II on-campus training program for American, French and British pilots. To accommodate such a vast effort, a variety of new airfields—literally converted cow pastures and cotton patches—were laid out in the countryside around Tuscaloosa to provide practice areas. Bryan directed the training of the teachers needed for both the flying and ground school instruction. When necessary, he and the other engineering professors taught the soldiers themselves. He couldn’t have guessed at the time that this would be the beginning of a 60-year stay at the Capstone, during which he never stopped teaching.

Dr. Hobson Bryan, Colgan’s son, who is a faculty member in the geography department, said aviation played a large part in his upbringing. “I can remember playing in the wind tunnels as a young child,” he said. “I was really impressed looking at the wing design and air flow.” Hobson also recalled the large collection of model airplanes and various replicas his father had on display at their home.

As preparation for the war increased, many of UA’s students were either drafted into or volunteered for the military. “Due to the need to build and maintain air power, aeronautical engineering students were allowed to remain in school and graduate before beginning military service,” Karr explained. It was deemed that they would be more valuable to the war effort if they had completed their degree. “Also, AE instructors and those involved in flight training were in critical demand,” he added.

The war caused a major change in the distribution of students among the engineering departments. As the Allied nations prepared for battle, aeronautical engineering enrollment at UA nearly tripled from 1937 to 1943. When the United States entered the war in 1941, 40 percent of engineering enrollment was in the AE program, according to Karr. It faced the daunting task of satisfying the greatly increased demand for an effective pilot training program.

Colgan Bryan met the challenge with the help of professors borrowed from other disciplines. In those days, Bryan and others worked long hours, usually seven days a week. Several thousand soldiers completed pilot training at the Capstone with only one accidental death: a student crashed his airplane while showing his skill near the home of a girlfriend.

Although Hobson Bryan was born after the war, he recollected the stories his father shared about this period of his life. “During the war, he told us, he was involved in classified activity,” he said. “But he was the guy that you would trust a secret with—he would never talk about exactly what he did.”

As war activities decreased, the AE program shifted its focus from pilot training to the scientific aspects of aircraft design. Then, in 1958, the department began adding faculty who specialized in space research and training, after Dr. Wernher von Braun’s group of rocket scientists arrived in Huntsville, Ala., and the boundaries of flight were pushed far beyond the skies.

Bryan continued serving the University for six decades as a professor of aerospace engineering and mechanics and as a consultant in aerodynamics for government projects for NASA, the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Army Missile Command, Boeing and the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics. He died in 2006, still doing what he loved. “It was amazing that he was in such demand as a consultant,” said his son. “He truly lived his life through the aviation industry, and actually lived to be 96.”

He vividly recalled his father’s lifelong dedication to his profession and to the University that became his home. “He told a lot of stories about how he thought an engineering education was fundamental, and that the University should be at the forefront of this kind of education,” he said. And the passion for the field continues in the family—Hobson’s son is completing his fourth year as an engineering student at Washington and Lee University.

(Article title from the poem High Flight by John Gillespie Magee Jr.; background from Aeronautics and Aerospace Engineering at The University of Alabama by Colgan H. Bryan and Charles L. Karr and A Promising Field by Robert Norrell)