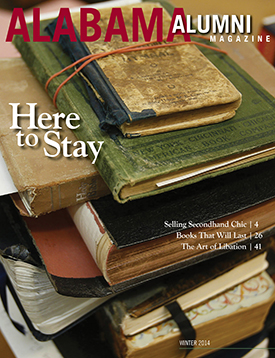

This rare business still binds books one at a time and repairs damaged ones from across the country with equipment from long ago.

by Becky Hopf

It is irony at its delightful best. One of Tuscaloosa’s oldest businesses is in the business of giving new life. The Tuscaloosa Library Bindery traces its start to 1924—at least that’s the earliest documented proof owner Jim Rosenfeld said he and his relatives have ever uncovered. It’s been in his family since 1955.

“A gentleman named Mr. Elliott actually started the business,” Rosenfeld said. “I’m not sure exactly where it was, somewhere in Alabama or Mississippi. He moved it to Tuscaloosa around 1936. It was known as Elliott Library Bindery. He was only here a year or two, and then a man named Clakey Bell bought it from him and renamed it Tuscaloosa Library Bindery. It was located near Bryant-Denny Stadium. Mr. Bell expanded it and moved it to 2122 Broad St., which is now University Boulevard.” Its home since 1964 has been 2704 Sixth St. in downtown Tuscaloosa.

The only business of its kind in Alabama, its long, open workroom contains stations of tables stacked high with books, magazines, newspapers and theses, each awaiting its next stage in being bound or mended, sometimes by a simple gluing or sewing repair to the spine, often by rebinding—adding a protective hardbound woven fabric or leather cover.

“We do a little bit of everything,” Rosenfeld said. “We’re not big enough to turn things down. It runs from the standard meat-and-potatoes of books and periodicals for libraries to family histories and genealogies. We do repairs on books of every kind: dictionaries, Bibles, cookbooks, scrapbooks, comic books, old children’s books.”

He estimates that the bindery processes about 25,000 projects a year. The rare books and volumes that cross the threshold are as fascinating as the fact that some of the equipment the bindery still uses today is more than a century old. There’s a page rounder and a backer made in the 1920s and 1930s, a board shear and a standing press from the 1920s, an antique Ludlow hot-lead casting machine, a trimmer from the 1940s and a book press that dates to around 1900.

“It was the same type of binding when they started out that we’re still doing—periodicals and old books for colleges and universities, public schools and public libraries,” Rosenfeld said. “That’s the nature of this business: was then and is now.”

His father, E.W. “Enie” Rosenfeld, bought the business from Bell’s widow. Enie was working as a clerk in the Tuscaloosa probate judge’s office when he saw Bell’s will come through. Having a retired uncle who’d once told him if he ever found a good business to invest in, he would, Enie decided the bindery was that perfect business.

Clearly it was.

Bell’s widow sold him the bindery and stayed on about a year teaching him the trade. She died a year or so later, forcing him to run with what he’d learned.

It was a never a given that Jim Rosenfeld would take over his father’s business. In fact, he said, his father at times tried to talk him out of it. “I’d been running around the bindery since I was old enough to remember. I started working there in the summers when I was about 12 and then full time in 1976. I was just a worker there, doing a little of everything. I guess it’s in my blood. It wasn’t ever a planned process of succession. I think my dad understood that if I found something else I wanted to do, I’d do that.

“My dad died 30 years ago, and that’s when I took over the operation. It’s challenging. It’s a living. I didn’t have his experience to draw on anymore, but I’d been there long enough that I felt comfortable with it.”

In the early days, Rosenfeld remembers piling into a truck with his dad to make pickups and deliveries as far away as Columbus, Mississippi, with Mississippi University for Women as a client. Now, clients ship material from all over Alabama and Mississippi, and across the country, from Colorado to Massachusetts. The bindery even has a client from Polynesia.

Summers were, and still are, its busiest season. That’s when schools send material to be bound. School libraries save money by buying paperback books and sending them to the bindery to be covered in a clear coating that converts them into hardbacks that will extend years to their life. Textbooks are sent for repair as well. And the busiest time of year also requires the quickest turnaround. Schools send the books in May or June, when classes end, and expect them back by August, when the new school year begins.

With an appreciation for history, Rosenfeld treats each item as a treasure. And his business has seen its share of treasures come through its doors. The bindery repaired a 200-year-old Bible, and recently, a 1912 Black Warrior High School yearbook, whose senior class of 15 included Clara Verner and Woolsey Finnell, who both have Tuscaloosa landmarks named after them.

Each item that arrives for repair is first studied to determine the best method for restoration. Materials often require a 10-step archival-quality process of about 41 separate operations that includes painstakingly taking apart the spine or existing page attachment, redoing the binding, cutting and scoring pages, gluing, adding covers and lettering. Typically, each item takes three days from start to finish.

“I’m a preservationist at heart. The things that we bind are going to outlast me and be available for future generations,” said Rosenfeld, who works with a full-time staff of six, some of them for more than 40 years.

He cannot remember a time when The University of Alabama wasn’t a client. There are no records for him to search to discover how far back the association goes, but he feels somewhat safe in assuming their history together dates to the bindery’s beginnings.

“The University has been very important to this business,” he said. “It has been one of our main clients forever. It’s always been a very good relationship, I believe—certainly good for us and very good for them.”

Rosenfeld attended Springhill College in Mobile his freshman year, then transferred to Alabama. But after two years, 1972–74, he left to go to work full time at the bindery. “My dad had gotten up in years, and his health was declining,” he explained. Leaving school was a difficult but necessary choice.

His family ties to the University date to the 1940s, when his mother, Lucille Wyman Rosenfeld, taught physical education at UA after World War II. She continued teaching until the 1950s, when his sister, Lucy Rosenfeld Sellers, was born. Sellers, who is now the principal at Northport Elementary School near Tuscaloosa, holds several degrees from Alabama.

Although his father didn’t attend college there, he befriended its most famous employee—Paul W. “Bear” Bryant. “My dad and Coach Bryant were friends and golf buddies,” Rosenfeld said. “Back in those days, Tuscaloosa was much smaller. It was something, at the time, that wasn’t as big a deal. Then Coach Bryant was just one of my dad’s friends who happened to be the football coach. They had a group that included Harry Pritchett (the University named its former golf course after Pritchett) and George Shirley, who were all close to him. What always impressed me about Coach Bryant on the golf course was they treated him not like the celebrity he was and grew to be, but one of the guys. They didn’t cut him any slack.”

Jim Rosenfeld is a charter member of Tide Pride, the University’s athletics donor program, and has served a couple of terms as president of Grand Slammers, the Crimson Tide’s baseball booster club.

His employee roster has included the occasional UA student. He remembers, in particular, a couple, Stephen and Joy Rotz, who were in graduate school at UA and worked for him two summers in a row, around 2006 and 2007. And sometimes students in the University’s MFA in Book Arts program will drop by to observe the binding process.

About a quarter of his business comes from UA, along with The University of Alabama at Birmingham, he said. Before technology made it possible for graduate dissertations and theses to be stored forever in an electronic format, his was the go-to place to have them bound. Some academic departments still require a paper version to be submitted, and the bindery handles several thousand a year.

The range of other items they bind for the University fills a spectrum. There are periodicals and special collections from the libraries; the School of Music sends scores for protective hard covers; and the Crimson White’s newspapers are bound into giant books with hardback covers for archiving.

As a fan of the Crimson Tide, Rosenfeld admitted that sometimes he takes a moment to look through items that cross his desk from the Bryant Museum and the athletic department. “I don’t have time to stop and look at everything that comes through, but every now and then, something comes through that catches my eye and jogs my memory about a particular game played or an athlete or coach,” he said.

In fact, his work with the Bryant Museum led his family to make a donation. “I’ve donated a few old programs that they didn’t have to fill in their collection, things my mom had when she passed away,” he said.

His business draws the occasional hobbyist—someone who binds their own books and wants to learn more about technique, types of glues and cover boards. But for Rosenfeld, who doesn’t see retirement anywhere near in his future, what he does is far from being a hobby. It is a calling.

“Anybody who stays in this business has to have a sense of the importance of legacy,” he said. “It’s like someone who restores old cars or old furniture. You have a respect for those items. You want to make them last so they can be passed on.”

Becky Hopf is a sportswriter, sports publicist and freelance writer based in Tuscaloosa.

A portion of this article originally appeared in Tuscaloosa magazine.