Some favor the ocean’s exotic surroundings for both work and relaxation, spending much of their time fully immersed.

by Mary Cypress Howell

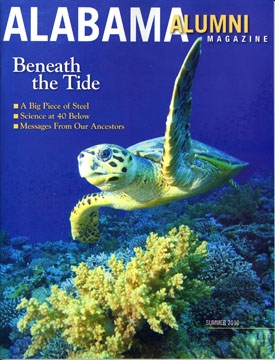

It’s not like jumping into a swimming pool—it’s like jumping into a different world. Diving deeper and deeper, you’re greeted by a rainbow of fish and curious sea turtles. While coming face to face with the smallest seahorse and the largest whale may be strange encounters for most people, for some University of Alabama students and alumni, this underwater world feels just like home, as their favorite setting for research and recreation.

One of these undersea enthusiasts, certified scuba diver Anne Davis Hasson, along with her husband, Wayne, wanted to make diving available for others to enjoy. The couple developed the first fleet of “live-aboard” scuba diving yachts.

Located in the best diving spots, the Aggressor fleet has yachts stationed at various locations around the world. From Belize to the Cayman Islands to Hawaii and more, these vessels allow divers to experience all types of marine environments, according to Hasson, who attended the University from 1978 to 1980.

“I’ve seen everything from 40-foot whale sharks to tiny sea horses. At Bloody Bay Wall in Little Cayman, you can see friendly turtles, sharks, stingrays, crabs and huge lobsters,” she said. “There are areas around the world that are getting fished out, but at places like this you can see everything.”

At Cocos Island, Costa Rica, hammerhead sharks and whale sharks abound, and divers are sure to encounter big animal action, according to Hasson. “Diving with hammerhead sharks is really exhilarating,” she said of this location, where her mother has even dived with her. “The sharks are pretty skittish. They are not attackers like a lot of people think.”

But these diverse diving opportunities aren’t what sets the Aggressor fleet apart from others—it is the concept of having guests live on board the boat during their diving expeditions. In 1984, after a decline in the oil industry, the Hassons encountered a man who was looking for a buyer for an oil-field boat. With experience in scuba diving and boat building, the couple decided to renovate the vessel into a livable dive boat. “We thought we’d do one boat,” Hasson said. “We never dreamed it would be a fleet; but one led to another, and it grew from that.”

The Hassons revolutionized the live-aboard diving boat. “We were the first real innovators of live-aboard scuba diving,” she said. “We took it from being a boat that people spent a week on with two shower heads and bunk beds, to a yachting business.” In honor of this distinction, and of her efforts to spur the growth of the industry and her innovative programs to keep divers diving, Hasson was inducted into the 2010 Women Divers Hall of Fame.

And the Aggressor fleet is not just for experienced divers. Anyone aged 10 years old or up can come on board one of the boats and learn to dive during the seven- to 10-day trips. A family week is offered once a year, where anyone 5 years old and up can join in. The younger children can snorkel while the older ones train to become certified in scuba diving.

With a high-repeat clientele, Hasson said they try to offer other activities as well. For instance, instructors are available to teach underwater photography on each of the boats. Along with being a photographer herself, Hasson is also an underwater model, and has been featured in many magazines, including National Geographic.

In addition to these services, the Aggressor fleet goes even further, as a world leader in preserving the oceans. In partnership with Jean-Michel Cousteau’s Oceans Futures Society, it offers programs to teach experienced divers about important ecological and biological concepts. The society, headed by the son of famed ocean explorer and scientist Jacques Cousteau, has a mission of exploring the global ocean in order to inspire and educate people to act responsibly for its protection. The Aggressor boats also establish reef moorings to help with underwater conservation.

The Hassons are not the only divers concerned with the status of the life below sea level. Carl and Elizabeth Midkiff, who own the CoCo View Dive Resort on the island of Rotan, Honduras, often hear concerns about the health of the reef in their area.

Over the next few summers, Carl Midkiff, a 1971 UA graduate, plans to host interns from his alma mater to conduct research of the reef. “Rather than sitting around talking about the reef, organized efforts need to take place to monitor its health,” Midkiff said. “If the reef declines, business declines; so it came up that this would merge perfectly with marine science at UA.”

The Midkiffs contacted Dr. Julie Olson, an associate professor in the UA biological sciences department, to establish an internship for students to do hands-on biodiversity and water-quality surveys. “One of the requests of Elizabeth was that people who come are divers, have an interest in marine environment and the health of it,” Olson said.

Julia Stevens, a first-year graduate student in biological sciences, will be leaving the Capstone this summer to stay at the Midkiffs’ resort and study the local reefs. “I applied to this program for the opportunity to do field work in my area of research. Julie Olson’s coral reef surveys are an important method for the monitoring of reef health, and more specifically the presence of coral disease,” Stevens said. “I am anxious not only to learn the field methods, but the stressors affecting this important ecosystem.”

Interns in the program will also be required to give presentations to the guests of the resort, educating them about the reef in 20-minute talks about coral diseases, what happens when an organism not native to the environment gets loose, and more. “It’s a fantastic opportunity to get hands-on experience in a beautiful environment,” Olson added.

Stevens said she is excited about doing research in one of the largest reef systems in the world, plus all the scuba-diving experience. The CoCo View Resort boasts some of the best diving and snorkeling in the world, Carl Midkiff noted. It is located on the reef, so guests can dive 24 hours a day without needing transportation out onto the water. And twice a day a boat is available to take divers to neighboring reefs.

Interns can also join resort guests in other activities, such as visiting the mainland to explore Mayan ruins, taking a zip-line through the mountains, riding horses around the island and white-water rafting.

Along with being a valuable experience for the interns, the program will greatly benefit the resort, according to Midkiff, who said he would hate to see anything happen to the reef. “Their knowledgeable input about wildlife and the health of the reef gives us detailed, authenticated results,” he said. “And the student has full exposure on a day-to-day basis of what they’re doing before entering the real world.”

Olson will accompany Stevens at the resort for the first week to set up transects that will be used for many years to measure the quality of the water, biodiversity, and coral and fish surveys, and to determine which dangerous bacteria are present.

Another UA student is involved in underwater research, but without getting wet—she enlists the help of high technology. Robin Cobb, a marine-science graduate student, recently returned from a cruise where she operated a joystick to remotely direct a research submarine as it hovered above the Atlantic Ocean’s floor, some 2,000–3,000 feet below the surface. Cobb traveled on the ship Pisces, from April 8 to 14, with scientists from six other institutions, using an unmanned submersible to study the deep-sea corals. The goal of this National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration program was for researchers to have an opportunity to collect exotic corals and photograph other rarely seen organisms on the ocean’s floor.

Cobb’s UA adviser and research mentor, Dr. Fred Andrus, assistant professor of geological sciences, previously participated in similar NOAA expeditions to deep-sea coral grounds off the coast of Georgia. Deep-sea corals and fisheries are areas of profound concern for NOAA, he said, because humans are beginning to have major impacts on them.

He and Cobb are studying rare Stylasteridae corals, found in very deep, cold waters, far below the level where light can penetrate. “They don’t fit the general knowledge of corals, but they play a role in fish that are commercially important,” Andrus said. “They record chemical information, and if we can figure out the chemical language they speak, we can measure chemicals in their fossils and see the way it has changed over time.”

Andrus explained that although the corals can give important clues to deep ecosystems, nobody before has made long-term observations of them, as few are found in shallower waters, and humans cannot survive in the ocean depths where they typically grow. These excursions are a lot like detective work, he said, but the sleuthing is in an exotic environment. “This is like working on the surface of another planet,” he added.

Cobb reported that during the cruise, the current was too strong to get the coral samples she was hoping for. However, she was able to collect fossils and water samples that will aid in their research.

This new material, added to past collections, will expand their knowledge when Cobb interprets her findings this summer. “It’s hard to get any deep-water information, and even water samples can be used to determine if we can use corals to determine ocean temperatures,” she said.

“[Robin] is seeing that these corals grow significantly different from any other coral we’ve seen,” Andrus said. “It seems that the interpretation of any data is going to be far more challenging than we thought.”

Cobb plans to do research on another cruise next fall, and until then, she will continue working with the samples at hand in an attempt to translate the coral’s chemical language, deciphering the mysteries of the underwater world.