by Alexandra Battito

The separate leadership efforts of two graduates of The University of Alabama have affected nothing short of miracles in child advocacy, improving lives of children across the state. Jim Ray is the executive director of Children’s Harbor, offering counseling and camp retreats to young people with serious illnesses and their families, and Marian Loftin is the director of the Alabama Department of Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention. Both Ray and Loftin have dedicated a lifetime to giving help, hope and strength to the families who need them most.

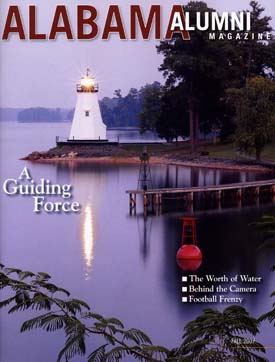

Lighting the Way

Among the handful of lighthouses that decorate the shores of Lake Martin outside of Alexander City, Ala., there is one with brightly painted white wood and a stout, sturdy frame, which stands out from its shady spot among the pines. It is Plymouth Lighthouse of the Children’s Harbor campsite, and it represents much more than meets the eye.

Adopted as an icon for the organization, the lighthouse is symbolic of how Children’s Harbor achieves its mission of providing support and reprieve for children who have serious long-term illnesses, as well as their families, said Ray.

“If you look at the strict interpretation of a lighthouse, the ships would never tread where the light fell,” Ray explained. “Our lighthouse is not only there to protect families and prevent additional problems. It’s also to light the way for families to find ways to a place of haven, a place of rest, and a place where they can distance themselves and find some relief from all the things that they’re going through.”

Like the lighthouse itself, Ray has also been with Children’s Harbor since it was founded in 1990, serving as the program director before becoming executive director in 1994. Today, Children’s Harbor works almost exclusively with children who have long-term, serious illnesses and their families. The camp retreats are only part of the services offered through the organization, all of which are completely free of charge.

“We try to put together a one-stop-shop kind of program for families with sick children,” said Ray. The Children’s Harbor Family Resource Center, which is connected to Children’s Hospital in Birmingham, Ala., is where families are offered counseling, as well as more tangible services when they’re needed, Ray noted. At the facilities on Lake Martin, children and families can relax and find relief from the medical environment.

After graduating from the University of Montevallo with a bachelor’s in social work and a master’s in education, Ray began his career working for the United Methodist Children’s Home in Selma, Ala. In 1984, he returned to school at The University of Alabama to earn his master’s degree in social work, graduating in 1985.

Ray gives major credit for Children’s Harbor to the couple he refers to as its catalysts and founders, Ben and Luanne Russell, who both graduated from UA in 1963. The Russells donated the land for the facilities in both Birmingham and on Lake Martin, and provided much of the funding for programs and buildings in the early days of the organization, Ray said. And for those who might wonder who’s behind the mask of Big Ben–the furry bear who has become the Children’s Harbor mascot—it’s all in the bear’s name.

Dozens of groups use the 50-acre Lake Martin campus to host their camp activities throughout the year. A few of these include Camp Smile-A-Mile, for children with cancer; Camp Conquest, for kids who are burn victims; and Wired Together, for children with heart disease. Children’s Harbor even hosts a few camps for adults, from those with cancer to the mentally disabled.

There are also plenty of special events offered. This year’s agenda runs the gamut, including rodeos, barbeque competitions, sporting clay and golf events-but the longest-running event is its annual antique boat show, Ray said. Even country music star Alan Jackson gets in on the action, he explained. “He’s an antique boat enthusiast and has quite a collection,” said Ray. “This is the third year we will auction a boat that he has donated.”

Ray and his wife, Marylin, are parents and grandparents themselves, with two grown children, Michael and Michelle, and four grandkids. “I think both the mistakes I’ve made and the successes I’ve had as a parent have helped me to be empathetic with what parents go through,” he said. “It’s just growing up and learning.”

In February, Ray was honored by the Alabama Conference of Social Workers with a Lifetime Achievement Award. Ray said he’s thankful to have been around long enough to see some of the positive effects that Children’s Harbor has forged on families’ lives.

“I’ve learned much more from families, I think, than I have given back to them,” he said. “But it’s been a good ride, and I’ve been blessed with the opportunity to do this.”

Strengthening Families

There’s a common thread of traits that Loftin seems to have carried with her through every role she’s played in life, from mother of four to her 17-year career as an elementary school teacher-warm energy, compassion and devotion to helping others live the fullest and happiest lives possible. Those same qualities shine through in her position as the director of the Department of Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention. And through her department’s management of the Children’s Trust Fund, that warmth can be felt all across Alabama.

“Neglect of children usually occurs because parents are unaware of child development—they often do not realize what their children need at different ages until they participate in some of our parenting education programs,” explained Loftin.

After graduating from UA’s College of Education in 1958 and teaching elementary school for nearly two decades, Loftin was appointed to the board of the CTF by Gov. George Wallace when it was established by the state legislature in 1983. Child abuse and neglect are serious matters that affect families in Alabama every day. The focus of Loftin’s agency, however, is not to heal wounded children and families, but to prevent abuse and neglect from happening in the first place, she said.

The agency does not provide any programs directly; instead, it allocates grants to proactive services in individual communities that will educate not only children, but more import-antly parents and caregivers. The overriding strategy of the CTF is to finance, monitor and give technical support to effective programs that are community-based as well as evidence-based, according to Loftin.

“Each community knows their needs and who would benefit from services locally,” she said. “It’s so gratifying to know that families are going to be better for what they learn in the programs, and that each child is going to be nurtured and loved, having the opportunity to become all God intended him to be,” she said.

Loftin’s agency supports and oversees a slew of programs for parents and children across the state, including some that stem from its partnership with UA’s College of Human Environmental Sciences. In a recent venture, the agency partnered with CHES and Patsy Riley, the first lady of Alabama, to create a child abuse prevention program called the Parenting Assistance Line. The toll-free, confidential hotline is based in the Child Development Resource Center on the UA campus.

Loftin’s department also partnered with CHES and the Center for Business and Economic Research in publishing a recent study on the estimated cost of child abuse and neglect in Alabama each year versus the cost of prevention. The results were staggering—an estimated $521 million is spent on the effects of child abuse each year in Alabama, for everything from hospitalization to law enforcement. “The first lady was presiding at our press conference after the results from the study were published and she said that it was overwhelming to think of what we, in the state, could do in prevention with over $500 million,” Loftin recalled.

Outside of the University and across the state, the programs that the CTF supports are as varied as they are innovative, but all of them share the goal of strengthening Alabama families. Classes on childhood development help parents understand how children behave at each age and how to deal with it appropriately. The Fatherhood Program, for example, focuses on non-custodial fathers, teaching them how to provide the best support for children even though they might not live in the same home. Other programs include Mentoring Children of Prisoners; the Alabama Community Healthy Marriage Initiative, emphasizing that the couple’s relationship affects a child’s well-being; and Lost in Cyberspace, educating parents about dangers on the Internet.

Earlier this year, Loftin was honored with the 2007 Commissioner’s Award from the Administration on Children, Youth and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Loftin said that receiving the honor was both an exciting and a humbling experience. “It was a special evening totally focused on how we can make this state and our country the very best place to raise our children,” she said.

Loftin has done her fair share of parenting in her lifetime as well. She and her late husband, Jim D. Loftin Sr., ’89, have four grown children: Valerie Shelvin, ’81; James Loftin Jr., ’84; Courtney Loftin; ’89, and David Loftin; as well as six grandchildren.

Though she has dedicated most of her life to helping children and their families, Loftin has no plans of slowing her involvement any time soon. “I think I will always have an interest in advocating for strong families and safe children,” she said.

To receive four issues of the Alabama Alumni Magazine each year, Join the Alabama Alumni Association Online