The genre of legal fiction has endured for centuries, and UA is playing its part by preparing writers, bestowing honors and lending inspiration.

by Haley Herfurth

Author Harper Lee once said that if one is going to write, he “should write about what he knows,” because the truest version of reality is the one you jot down after you’ve walked through it. The mind of a fiction writer is a great card catalogue of sorts, with every happening filed away just to be pulled out later, to be seen again in the form of scenery or a plot point or character flaw.

Some re-form experiences into the abstract, while others base whole novels on pieces of their lives, like Lee in her 1960 classic To Kill a Mockingbird, or popular novelist Michael Connelly, who became drawn toward detective stories after witnessing a crime as a child and spending a night in a police station as the investigation began.

Legal fiction writer Robert Bailey’s book The Professor is an amalgamation of many of his life experiences, including his education at UA’s School of Law and a lifetime of yelling “Roll Tide.” But perhaps what has informed him most is his 15-year career as a trial lawyer: “When you are trying cases in front of a jury,” he said, “you are telling them a story.” At the heart of it, you are telling them what you know.

Bailey graduated from UA with his law degree in 1999, moving back to his hometown of Huntsville, Alabama, to practice with Lanier Ford Shaver & Payne PC, where he’s worked ever since. He’d only been out of law school a year when he began writing the first—of three—drafts of The Professor, a legal thriller that tells the fictional story of longtime UA law professor Thomas Jackson McMurtrie, who gave up a promising career as a trial lawyer to teach at the request of his mentor and former coach, Bear Bryant. When the young family of one of his oldest friends is killed in a collision with an 18-wheeler, McMurtrie enlists the help of former student Rick Drake, who soon uncovers a tangled web of arson, bribery and greed.

“It’s a legal thriller, but at its heart and soul, it’s a story of redemption,” said Bailey. He chose to incorporate a quasi-fictionalized Bryant into the book because, when you’re raised in the South, the Bear is already a kind of legend, he said. “I grew up an Alabama fan, where you are bathed in stories of Coach Bryant and those who played for him,” he explained. “It was fairly easy to picture him, having heard and seen so much of him on TV. I remember when he passed away. They shut school down. It was like the president had died.”

Additionally, Bailey’s work as a lawyer has given him experience handling trucking cases, like the one mentioned in The Professor—“I know a good bit about that,” he said—and his extensive background in the field helped him write the technical aspects. He added that his two professions complement each other nicely. “Being a trial lawyer has made me a better writer, and vice versa.”

In addition to serving as a setting for Bailey’s narrative, UA itself is firmly entrenched in the world of legal fiction writing. Lee, an Alabama native and arguably the best-known legal fiction writer of the modern era with her Pulitzer Prize-winning Mockingbird, attended the Capstone in the 1940s. In her honor and with her authorization, UA partners with the American Bar Association to present the Harper Lee Prize for Legal Fiction, given annually to a book-length work, published in the preceding year, that best illuminates the role of lawyers in society and their power to effect change. The award has been given for the past four years; winners include Havana Requiem by Paul Goldstein, Sycamore Row and The Confession by John Grisham, and Connelly’s The Fifth Witness. According to Monique Fields, manager of communications for the School of Law, administrators are not aware of another similar honor that competes with the Harper Lee Prize.

“It’s a huge honor for the School of Law to be associated with Harper Lee in this way,” said Dean Mark Brandon. “But more importantly, it signals to the world something of the values we embrace: community, human dignity and the highest values of law and the legal profession.”

While Lee’s classic has become perhaps the most recognizable and popular legal novel, the genre can be traced back centuries, to Parisian lawyer Francois Gayot de Pitaval’s Famous and Interesting Cases, published in 1735, a 22-volume collection of memorable cases from centuries of French history.

In 1841, Graham’s Magazine published Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue, the quintessential piece of detective fiction and murder mystery. Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, published in 1859, is largely considered one of the first legal thrillers—called at that time a “sensation novel,” which brought together in one narrative an innocent person, a detective, the legal system, conspiracy and suspense. Contemporaries of Lee’s include John O’Hara and Allen Drury; the 1980s and 1990s saw the rise of Steve Martini, Scott Turow, and 2011 and 2014 Harper Lee Prize-winner Grisham.

Despite often morphing between the categories of crime fiction and mystery, it’s clear that the legal thriller will continue to thrive. “It explores the justice system. It teaches,” Connelly, the 2012 Harper Lee Prize-winner and a graduate of the University of Florida, said of the genre. “The non-lawyer may have a difficult time reading a legal brief, but a human story about the factors in that legal brief can connect one to one with a reader. It can take legal concepts and theory and give them a flesh-and-blood reality.”

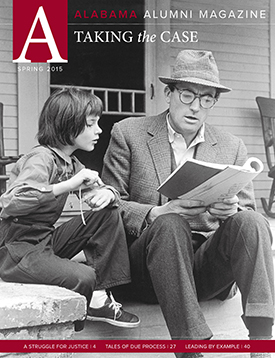

Legal fiction can also be a good channel for discussing thoughts on social or political issues, Connelly said, though it is important to do so with what he calls “finesse.” “If you think there is a particular issue in the system that needs to be addressed, then you think up a scenario that will take your character right into that room,” he said. “And then rather than talk or preach about it, you show it.” Many consider this to be what Lee did with Mockingbird—she raised issues related to Southern life, social injustice, classism, racism and gender roles, but rather than preaching to her readers, she set scenes where characters like lawyer Atticus Finch addressed the issues in a more nuanced manner.

In various ways, Lee used parallels of personal experiences in her novel; like she advises, and like Bailey did, she wrote about familiar things. As an author of more than two-dozen novels that span detective, crime and legal fiction, Connelly said that, much like Bailey and Lee, his personal experiences have served as inspiration to him. In addition to his childhood memory of the police station, he calls on recollections from working as a crime reporter in Florida and Los Angeles in the years following his graduation. He had grown up in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, where one of his favorite authors, John D. MacDonald, set many of his crime novels. “I even had a summer job at Bahia Mar, where the fictional detective docked his houseboat,” Connelly added.

The Lincoln Lawyer, Connelly’s 2005 novel that was made into the 2011 film of the same name starring Matthew McConaughey, was his first venture into legal fiction; his prior books were considered crime novels. This was his 16th book, but Connelly said the transition was fairly simple. “In a way, it was like moving to a different position on the team,” he said, “like going from shortstop to second base. It was close but also very different.”

While Bailey said his law background made writing The Professor easier in some ways, Connelly said that not being a lawyer pushed him to work harder on his finished product. “What made the transition was not being a lawyer and knowing that many lawyers would read and probably critique the book,” he said. “So I really had to do much more research and fact-checking to make sure it didn’t come off as having come from a complete amateur.”

His resolve to write convincingly and entertainingly within the genre earned him the Harper Lee Prize three years ago, which he said was an honor. “Being a non-lawyer, it was very special for me to receive it,” he said. “It told me that all the time invested in research, sitting in courtrooms, having lawyers vet the books, is all worth doing.”

Mockingbird’s influence extends from the social, legal and artistic world into the academic; while law school dean Brandon’s schedule is often too hectic to allow much time for reading, he said he does enjoy legal novels, particularly books by Grisham. However, he said he has a special affinity for Lee’s book. “I can’t think of a work of legal fiction that’s had a greater impact on me than To Kill a Mockingbird,” he said. “The elegant rhythms of language and the quiet, poignant, heartbreaking beauty of the story are unmatched in my view. The book is an achievement.”

Bailey, who plans to enter The Professor for the 2015 Harper Lee Prize, said he read her novel when he was young, and it impacted him in many ways. Connelly said a librarian encouraged him to read the classic when he was 12, and that “it has been engrained in my creative mind thereafter.

“Every lawyer in Alabama wants to be Atticus Finch,” Bailey said. “And in a way, all writers are inspired by that book.”

Lee’s writing career seemingly began and ended with To Kill a Mockingbird, her only published work, until she recently announced plans through publisher HarperCollins to release a second novel, originally written in 1950, which catches up with the same characters 20 years later. Her fans were ecstatic, and a bit stunned, after a 55-year wait. But both Bailey and Connelly intend to keep going strong, with no hiatus in sight.

Between the first and final drafts of The Professor, Bailey wrote a second book, Between Black and White, which he plans to publish as a sequel.

In February 2015, Amazon Studios released the first season of Bosch, based on Connelly’s 21-book Harry Bosch series, and he said that, while he was very involved in helping create the show, writing is his first love. His novels have sold more than 58 million copies worldwide, and he has won numerous writing awards, including the Edgar Award (named for Poe), the Los Angeles Times Best Mystery/Thriller Award and the Nero Award, among others.

“I am a book writer first,” he said. “My hope is that the show will lead people to the books, because that is what I do. I did spend a lot of time on the first season of the TV show because I really wanted to establish the character and world of the show. It was great fun and very interesting and fulfilling, but when we wrapped on the season, I was happy to go back to writing a book.”

Some details were referenced from “Collins to Grisham: A Brief History of the Legal Thriller,” by Marlyn Robinson, published in Legal Studies Forum, 1998.