Getting attention for a worthy subject might best be accomplished with a video camera, a clapboard, a script and a vision.

by Lawrence Specker

For Kaitlin Smith, the moment came as she walked to a film class, when she decided it was time to “go big or go home” with a story of heroism amid the devastation of Hurricane Katrina. “I just said, ‘You know, I’m going to pitch a Coast Guard documentary,’” she recalled. “And so I did, and I can’t believe I did it. I thought it was crazy, like why would I do this, because logistically speaking, I can’t do this as a student. There’s no way.” She found a way.

For Dr. Jennifer Lewis, the moment came long after graduation, working as a scientist and warily watching public discussion of topics such as climate change and evolution. “I was always really worried about scientists not getting their messages across to the general public,” she said. “I was watching things happening, and thinking, we are losing huge battles that we shouldn’t be losing.”

The two women’s stories are very different, yet those moments gave them some things in common: a shared commitment to documentary filmmaking and a passionate belief that stories have the power to make the world a better place.

The Conservationists

For Lewis, the insights came gradually. After earning a master’s degree in marine science at The University of Alabama in 2002, she pursued a doctorate at Florida International University and went on to work with the Tropical Dolphin Research Foundation. “After I finished my dissertation at FIU, I kind of felt like I might have the ability to advocate a little more if I wasn’t at a university, per se,” she said. “And I could maybe have more power to do things quicker if I started a foundation.”

She had the sense that things needed to happen more quickly. “There’s about 23 different dolphins that are ranging either entirely or partially in the tropics, and there’s a lot of reasons that we were worried,” she said. “One of those is that the models from climate change are showing that’s the area on the globe where they expect the biggest loss of species diversity and species richness. The other big thing, the major thing, is when you look at that part of the globe, it covers mostly developing countries that don’t have resources.”

Lack of resources translates into lack of research. Lewis cited the “Red List” of species status maintained by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. “If you look at most of those species that are in the tropics, for dolphins, it says ‘data deficient,’ ” Lewis said. “And chances are, the ones we do know about are critically endangered. We felt like that was really where we should be putting our time and focus.”

She took note of documentaries such as Oscar-nominated Blackfish, which is critical of keeping killer whales in captivity, and Oscar-winner The Cove, an exposé of Japanese dolphin-hunting practices. “I started to see the power of that particular type of media for getting these discussions going,” Lewis said.

But when she launched her own project, Who Will Save the River Dolphin, in late 2013, she took less of an activist approach, focusing at least as much on people as on animals. Her work in progress isn’t just about the Ganges River dolphin; it’s about young conservationists in India, Nepal and Bangladesh and the varied challenges they face.

“It turns out it’s an enormous struggle for these young people in Asia to stay in conservation,” she said. For one, it might be that his family doesn’t want him to pursue graduate studies. For another, it might be the possibility that an arranged marriage could derail her work. For someone else, it might be the need to work within a region where organized crime affects the health of a river and any conservation effort must engage the criminals as stakeholders. For all, it’s a struggle to raise awareness that the river dolphins even exist and are worth preserving.

“Our goal is to show it in every one of those countries where the dolphin is found,” Lewis said. “I don’t expect it to change the world, by any means. But we’re hoping it can educate and start discussions in maybe a way that we could not do from any other method.”

A trailer for the film can be found at vimeo.com, and a journal about the experience is posted at theriverdolphin.blogspot.com. Editing the project will take at least until the end of 2015. After that, Lewis said, she’s hopeful to screen it at film festivals and eventually gain distribution via public television, Netflix and other channels.

Always Ready

Kaitlin Smith won’t have to wait that long for her film to find a mass audience. The documentary that she began as a senior-year class project at UA in spring 2014 was scheduled to show on public television in three states at the end of summer 2015.

That’s a pretty incredible timeline. But when talking to Smith, it’s clear she’s not one to wait around when she’s got a goal in mind. The daughter of a Coast Guard officer, she thought that the service’s rescue efforts following Katrina formed an untold tale of heroism, one that she was determined to bring to light.

Katrina made landfall in Louisiana on Aug. 29, 2005; in its aftermath, New Orleans flooded and the Mississippi coast was scoured by a massive storm surge. The Coast Guard’s Air Station New Orleans and its Aviation Training Center in Mobile, Alabama, both were damaged, but both launched rescue efforts, and the Mobile base became a hub for the disaster response effort.

Smith had signed up for a producing class, but because it was over capacity, she and some other students switched to an independent study film class. Either way, her vision was far too large to be finished in a semester. But Smith had three things going for her: her passion, her connections to the Coast Guard through her father, and a professor who didn’t ask her to dial back her ambitions.

That professor would be Maya Champion, whose duties include serving as adviser for the telecommunication and film department. “If it wasn’t for her, I don’t know if I would be here today,” said Smith. “She gave me that initial push. And the whole thing is, we had to turn in a project by May of that year. And I did. I turned in footage. I turned in scripts. I turned in production binders. I kept going. And so I’m blessed to have her let me continue the project through the summer and fall and now.”

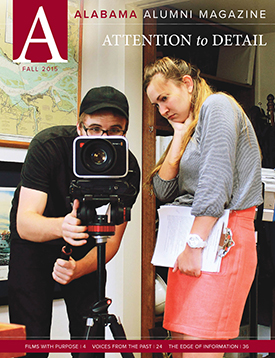

Champion said that her own film experience gives her an understanding of “the scope and scale” of projects, and modern digital tools give students the power to do more than ever. But not every ambitious classroom pitch gets a green light. “I constantly have to gauge students and their abilities,” she said. Some need to develop practical skills before pursuing their dream projects, and some need to find the passion that will carry them up the learning curve. “Kaitlin, I knew that she had the resources to do it,” she said. “So of course, why not do it?”

“As far as how I approach teaching, especially something like producing, it’s very practical; it’s very hands-on,” Champion continued. “I’m pretty encouraging of their ideas. I also teach that class with the thought that they are training for the real world of film.”

With that support, Paratus 14:50 was on its way to becoming a reality. The title refers to the Coast Guard’s motto—“Semper Paratus,” meaning “always ready”—and 2:50 p.m. (14:50 military time), when its first rescue after Katrina made landfall. It’s critical to mention that the documentary wasn’t a solo effort—far from it. Smith led a team that included a number of fellow UA students, and their contributions are detailed at the film’s website, paratus1450.com.

“I started my own business in March of 2014 to sign the agreements,” Smith said, referring to paperwork from the Coast Guard’s Motion Picture Office. “In April 2014, we were doing the logistics behind scheduling all the interviews; in May, we started filming, and we ended in August. And it hasn’t let off since.”

After traveling around the country to interview Coast Guard personnel who had been involved in the Katrina recovery effort, Smith came back to campus in the fall of 2014, and turned to UA’s New College for the next stages of the project. “You create your own classes, your own curriculum,” she said of the interdisciplinary program. “So I created a documentary storytelling class, and I created an advanced postproduction class, and I was doing the project all fall as a student.”

She graduated in December 2014 with a bachelor’s in communication and a documentary that was ready for post-production—or so she thought.

In late 2014 and early 2015, Smith ran a Kickstarter campaign through the Internet-based crowdfunding platform to raise money for the remainder of the work. Although the team was aiming for $3,000, donors gave almost $9,000. But the campaign had another impact: As more veterans of the Coast Guard’s Katrina effort became aware of the project, they also contributed information that made Smith rethink the whole thing.

“When we launched our Kickstarter, a lot of Coast Guardsmen around the entire service were sharing their stories from Hurricane Katrina. They were sending us photos and videos to use,” she said. Through these connections, they were finding new information.

“I found out more and more of what was happening, so we decided to rewrite the script. That took us all of January and February,” she said. In March, the team came back to Tuscaloosa. They edited all of March, April and May, completing the documentary on June 1, 2015.

“It was a sleepless day. I was up for like 70-something hours. Our crew doesn’t sleep anymore.”

That’s not a complaint. For Smith, it’s the lesson.

“My greatest advice that I could give to anyone, no matter what industry, is learn every aspect of that industry,” she said. “If you want to be a filmmaker, a cameraman, learn how to use audio equipment, learn about what a producer does, a director does, know what the editor does. Learn everything. I have been involved with every aspect of this, and they don’t teach you this in school. In school, they give you the tools. They teach you the terminology. But unless you yourself go out into the world and get the experience and want to learn, then you’ll never be successful.

“And it has been life-changing. I have learned so much in the last year and a half that it’s hard to even comprehend. It’s just unbelievable,” she said. “It takes over your life. I’ve sacrificed so much. I’ve sacrificed my family, I’ve sacrificed so many things for this documentary, and that’s because I have the passion for it. And in this industry, you need that.”

Paratus 14:50 was scheduled to air on Alabama Public Television on Aug. 26 and 30. Smith said she also expected it to air on public television in Mississippi and Louisiana in late August, near the 10th anniversary of Katrina, and she was hoping for a national broadcast. For her, that’s a payoff both personal and professional.

“I know I’m doing something good for these people,” she said. “My goal for this project was always to tell the story of this heroic rescue that the Coast Guard carried out. Personally, what I want out of it for a career goal is to continue making documentary films. It’s what I want to do in life.”

A Bigger Message

Lewis will wait a little longer before her own payoff, when her film about saving dolphins comes to life for viewers. But in the meantime, she’s paying it forward: Almost an accidental filmmaker herself, she’s encouraging her own students to make it a core part of their science.

“I teach it to all my students now,” she said. “I teach them as much as I know about filmmaking and how to use it.” It’s part of a bigger message, she noted: Whether through film or other means, scientists have to make an effort to talk to the public. They can’t just be content to talk to each other.

“They love it because it’s creative,” she said. “And we don’t ever get to be creative in that way, from an artistic perspective.” Lewis stressed that she’s not encouraging scientists to make propaganda. Instead, she’s coaxing them to share what moves them, just as she’s sharing the stories of young Asian conservationists who inspired her.

“One thing I have learned about filmmaking, documentary filmmaking, is you don’t really even know what the story’s going to be until you get there,” she said. “That’s what I do love about this, that part of it, the unknown.

“We’re wired for stories. Human beings love stories, and that’s a really interesting way of getting people to pay attention.”

Lawrence Specker, ’92, is a reporter for Alabama Media Group in Mobile, Alabama. Some details were referenced from AL.com’s coverage of Kaitlin Smith’s campaign to produce

Paratus 14:50.